Of all the many ways in which the All-holy Mother of God reveals Her mercies to men, there is one that stands out both as being undeniable (for it is a completely “objective” phenomenon) and as touching the heart in a most immediate way. This is the phenomenon of weeping icons, in which images of the Mother of God produce tears that arc exact replicas, on the scale of the icon, of human tears—originating in a corner of the eye and coursing down the side of the face, sometimes as distinct miniature teardrops, sometimes as a flood of tears that moistens the whole face.

![]()

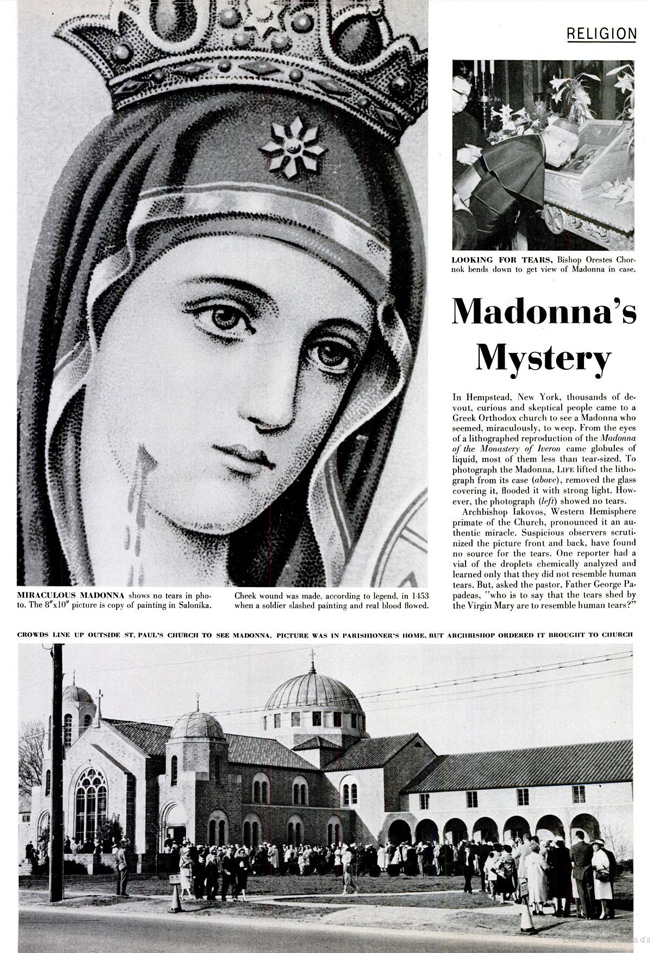

America too, so late to receive Holy Orthodoxy, is now the witness of this miraculous phenomenon. Three weeping icons[1] appeared quite suddenly, one after the other, within two weeks in the spring of 1960 among Greek families on Long Island, New York. The striking nature of this twice-repeated sign has drawn considerable attention to these icons, especially among Orthodox believers, but also among those outside the Church. Numerous articles have been written about them in American magazines and newspapers,[2] and in whatever cities they have appeared they have attracted large crowds of believers, as well as the simply curious.

The first weeping icon known in America was manifested in March, 1960, to the Greek family of Katsunis, living in Island Park, Long Island, New York. The young wife, standing at her evening prayers one Wednesday, noticed that one of her icons (the Mother of God without the Child) was shedding tears. She called her husband, and the two of them observed the phenomenon in awe. Others learned of it through a neighbor, and from Friday on began flocking to the modest Katsunis apartment. On Saturday the parish priest arrived and celebrated a service before the icon, and on the next day Archbishop Iakovos celebrated a service before it with two priests. Then the icon was removed to the church of St. Paul in Hempstead, where every Wednesday for a year there were services before it. The icon, an 8 × 10 lithograph, had been received by the young couple on their wedding two years before from a nun in Greece.

Four weeks later, in a house just four miles from the Katsunis house, Antonia Kulis had a dream during sleep. Christ appeared to her on the Cross and said: “You will see what will happen on Holy Thursday…” Antonia noticed tears for the first time on Passion Wednesday at about 2:30. The idea had suddenly come to her to burn incense and pray before her icons. She went with the censer into her daughter’s room, where the icons were—and froze to the spot, seeing tears in the eyes of the Mother of God. She called her husband, and together they called the priest, Fr. George.

This new weeping icon was also a simple 8 × 10 lithograph, printed in 1938, which had been received by Antonia from her cousin two years before. It was an icon of the Mother of God of Iveron, the original of which is on Mt. Athos. It differed from the earlier weeping icon in that tears came from both eyes and were more abundant. On Great (Passion) Thursday the icon, accompanied by nearly 1000 people, with Archbishop Iakovos at the head, was transferred to the same church of St. Paul where the first weeping icon was located; there a paraklis was served before the icon. During the services of Great Friday the flow of tears was especially noticeable. Many times it would increase. The Mother of God wished, as it were, to engrave this sign on the minds of all—even completely cold and sceptical observers. A photograph taken of the icon testified that the flow of tears, hardly noticeable in the beginning, visibly increased the very moment the picture was taken.

The second weeping icon evoked a heightened interest also on the part of scientific investigators. They could only testify to the fact, which, even if it did not make believers of them, they could not deny. An analysis was even made—as was done also with the first icon—of the fluid. It was discovered only that it was not of the nature of human tears. But the miracle continued. The Mother of God as it were paid no attention to these blasphemous displays of human curiosity.

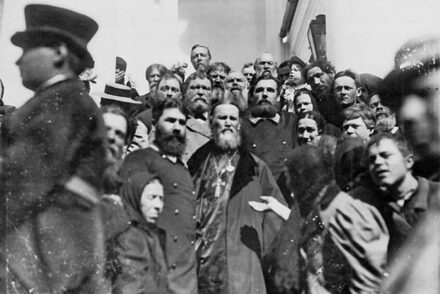

The number of people who came to see and venerate the second weeping icon by far surpassed the already large number that had come to see the first. Now the ever-growing crowds were to be numbered, no longer by hundreds, but by thousands; a never ending line of people extended far outside the church. On Easter Tuesday the late Metropolitan Anastassy, together with clergy of the Russian Church Abroad, came to revere the icon.

In place of the icon which had been placed in church, Archbishop Iakovos gave Antonia another lithograph-icon, that of the Mother of God “of the Passion,” so called because of the angels on either side who hold the instruments of our Lord’s Passion. Soon thereafter, on May 14, 1960, this new icon in its turn began to weep, and it too was taken to the Greek church in Hempstead. It was there a comparatively short time together with the first two weeping icons, during which time the icons were seen by a large number of people. Soon, however, the Mother of God appeared in a dream to the owner of the icon, saying: “I do not want to be here, take Me away; I want to be in your house.”

At the present time the first icon is located in the chapel of the Greek Archdiocese in New York City; the second icon is still in the church of St. Paul in Hempstead; and the third is in the possession of the Kulis family. All three icons have periodically been taken to Orthodox churches, both Greek and Russian, throughout America and have attracted widespread interest and veneration—especially the third icon, that of the Passion, which has shed abundant tears now for over five years.

The fact of the weeping icons is indisputable. Having witnessed it and accepted it, one is inevitably led to ask: what is the significance of this phenomenon? For signs such as these have a meaning in the language of faith which is the means of communication between this world and the other world. The response of devout Orthodox people and clergy who have seen and prayed before the icons points to a single, nearly unanimous interpretation of their meaning. But to corroborate this one must turn to the tradition of the Church, to seek there similar manifestations from the past, and to discover the historical role they played and the reaction to them of contemporary saints, hierarchs, and devout people. As it turns out, the phenomenon, though rare, is by no means without precedent in Church history. From Russian sources alone it has been possible to find nine examples, covering a period of eight centuries, before the most recent weeping icons; and these are doubtless not the only examples. They will be noted here in chronological order.

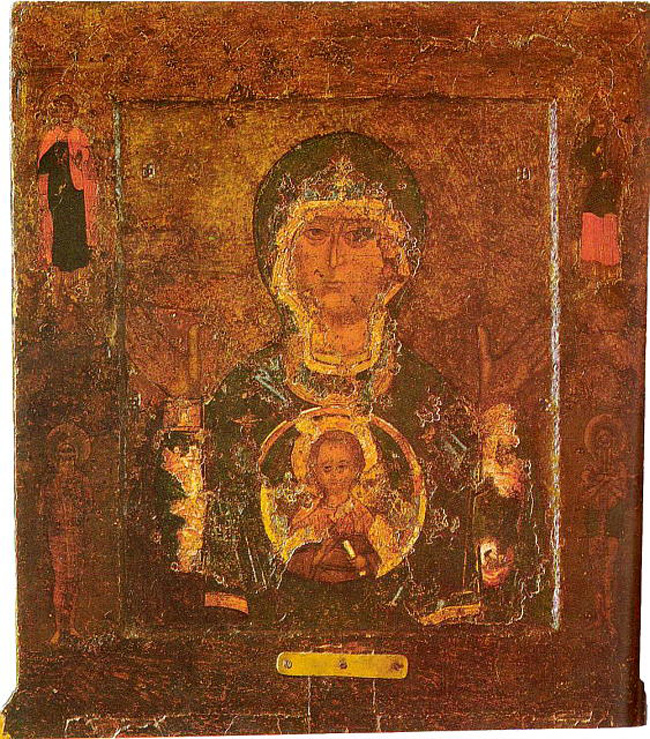

The Mother of God of the Sign, of Novgorod.[3] This icon became celebrated at the time of the siege of Novgorod in the 12th century. St. John, Bishop of Novgorod, was praying for the third night for the deliverance of the city, when from an icon before which he was praying a voice came, ordering him to go to a certain church and take from it the icon of the Mother of God of the Sign, from which was to come the salvation of Novgorod. This was done, and the icon was placed on the city wall with its face to the enemy. A veritable shower of arrows was falling, and suddenly one of these pierced the icon. The icon of itself turned toward the city, and from the eyes of the Mother of God tears poured forth. The holy archpastor took his chasuble and began to collect in it the tears which were dropping from the icon. He exclaimed: “O, most glorious wonder—from dry wood flow tears! By this, O Queen, Thou givest us a sign that Thou art praying to Thy Son and our God for the deliverance of the city.” The whole city began to pray fervently. An inexplicable terror fell upon the enemy; they were enveloped by a dense darkness and turned on each other. In this way the city was saved on February 25, 1170.

![]()

The Hodigitria of Cherska (or of Pskov)[4]. In the year 1420 a terrible epidemic broke out in the province of Pskov. The people in despair sought consolation in prayer to God and His Most Holy Mother. On July 16, in a church in the village of Cherska, there was a great sign: from the eyes of an icon of the Hodigitria Mother of God there flowed tears. News of this miracle spread quickly, and multitudes flocked to venerate the newly-glorified icon. When, under orders from the Prince of Pskov, the icon was transported to that city, the miracle was repeated as the Prince came to meet the icon, and the triumphal procession was stopped and a moleben of thanksgiving celebrated on the spot. The icon was then placed permanently in the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Pskov.

The Mother of God of Ilyin-Chernigov.[5] This icon was painted in 1658 by a monk, and was located in a monastery near Chernigov. For eight days in the year 1662 (April 16–24), the icon wept, of which fact the whole population of Chernigov were witnesses. St. Dimitry of Rostov testified that “on this miracle everyone in the city of Chernigov looked with great fear.” An historian of that time, Velichko, explained the reason for the weeping thus: By this means the Mother of God was revealing Her special love and mercy to believers who venerate Her icon, and also Her compassion for the miserable condition of the Orthodox Little Russians, who were suffering the misfortunes of civil war, captivity, and tyranny. In the same year the Tartars attacked Chernigov and laid it waste; here, apparently, was the specific reason for the tears of the Mother of God. The monks heard about this attack in advance and hid in the cave of St. Anthony of Pechersk; the Tartars destroyed much of the monastery but did not find the monks nor do the icon any harm.

![]()

The Kazan Icon of Kaplunovka.[6] This icon was revealed to a devout priest in the village of Kaplunovka, district of Kharkov, in the year 1689. In obedience to a dream which he had had several nights before, he bought from the third of three traveling icon painters the eighth icon he offered, one of the Kazan Mother of God. He placed the icon in his room and kept a candle lit before it day and night. In the night of the third Sunday afterwards, the Mother of God appeared to him in a dream and said: “Do not force Me to be in your room, but take Me to My church!” The church in Kaplunovka was dedicated to the Birth of the Mother of God. On awaking he went to the icon and discovered that tears were pouring from the eyes of the Mother of God. He immediately called the people and told them about the icon; and after a moleben had been served before it, the icon was triumphantly transferred to the church, where it was glorified by many miracles. Twenty years later the icon attained national significance when the Swedes passed through Kaplunovka in their invasion of Russia; Tsar Peter ordered the priest to travel with the miraculous icon in his army, and before the Battle of Poltava he prayed fervently before the icon. After the Russian victory the icon was taken to Moscow and then returned to Kaplunovka, Tsar Peter adorned it with a riza and a shrine.

![]()

The Kazan Icon of Tambov.[7] When St. Pitirim was Bishop of Tambov, he had a difficult time: the moral character of the city was low, and he had to fight much especially with new arrivals in the city. With this in view he had placed upon the two chief gates of the city two superb icons: one of the Crucifixion, and one of the Kazan Mother of God. The latter icon had been in the old Tambov Cathedral and had become glorified by a remarkable miracle. According to the Tambov Annals, “on December 6, 1695, during the all-night vigil in the wooden cathedral church, tears flowed from the eyes of the Kazan Mother of God…” It was probably after this miracle that the icon was ordered placed upon the city gate for the veneration of all. Many began coming to the icon to entreat help in their afflictions; veneration of the icon increased, though it apparently did not weep again, and there were healings.

The Sokolsky Icon of Roumania.[8] This icon of the Mother of God was located in the church of the Orthodox Theological Academy at the Sokolsky Monastery in Roumania. After the Liturgy in the seminary church on February 1, 1854, it was noticed that this icon was weeping. The rector of the seminary. Bishop Philaret Skriban, was among the witnesses of this miracle. He took the icon out of its frame, looked at it carefully, wiped the traces of the tears off with a cloth, and replaced the icon. He then asked all to leave, and he locked the church. When the rector, together with the teachers and seminarians, came to church for vespers several hours later, all were struck by the same miraculous flow of tears from the eyes of the Mother of God. The rector immediately served a moleben and acathist before the icon. Soon all of Roumania knew of the miracle and began streaming to the monastery to venerate the icon. News of it spread throughout Russia also, and found a place in a chapter (“God’s People”) of Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace—where it received a blasphemous treatment by the author, as ever unwilling to accept God’s grace. The miraculous flow of tears occurred sometimes daily, and sometimes with an interval of two, three, or four days. Many were thus able to sec the very miracle of weeping, and those who did not at least could see the traces left by the tears. Even sceptics became convinced of the miracle. A certain colonel was sent by the commanding officer of the Austrian occupation force (during the Crimean War) to investigate the rumored miracle, and to his astonishment witnessed the actual flow of tears. An important testimony of the miracle was offered by Bishop Melchisedek of Romansk, one of its first witnesses. Thirty-five years after the event, he spoke of how he had long pondered the question of the meaning of the tears of the Mother of God. He came to the conclusion that such weeping icons had existed also in ancient times, and that such an event always foretold a severe trial for the Church of Christ and for the nation. History justified this conclusion in the case of the Roumanian weeping icon. During the Crimean War the Principality of Moldavia was occupied by Austrian troops and subjected to severe trials. The Sokolsky Monastery, in particular, had a sad future: this formerly great religious center of Roumania, serving for a hundred years as a seedbed of spiritual culture, was suppressed, the seminary moved elsewhere, and the monks dispersed.

The Smolensk Icon of the Nizhegorod Caves Monastery.[9] In the life of the remarkable and holy starets. Hieromonk Mardary, there is the following incident: In the year 1854 a poor widow whose daughter was sick came to the starets to take oil from the lamp that burned constantly before the icon of the Smolensk Mother of God in the monastery church. The starets went with her to the church—and they saw tears streaming from the eyes of the Mother of God. Astonished, they prayed a long time before the icon without understanding what the tears signified. The widow wiped the tears from the icon with a cloth and brought it home together with the oil; the tears and the oil together healed the sick girl. The starets meanwhile told a monk about the tears and remarked: “This signifies something extraordinary; is everything all right in Petersburg?” Within less than a week word was received of the news that brought sorrow to all Russia—the reverses of the Crimean War.

The Tikhvin Icon of Mount Athos.[10] This icon is located behind the altar in the Skete of the Prophet Elijah on Mt. Athos. On Thursday of the second week of Lent, February 17, 1877, after the Lenten hours had been read, seven monks who remained in church saw plain traces of tears coming from the right eye of the icon and streaming down to the frame, where they collected; from the left eye, in the sight of all, a single large teardrop rolled down. The witnesses examined the icon carefully, wiped off the tears, and left the church, locking the door behind them. Three hours later the monks returned for vespers, and on the Tikhvin icon they again saw traces of tears and, in the left eye, a teardrop. The monks again wiped the tears from the icon, and after this the miracle was not repeated. In this weeping icon the monks saw a miraculous sign of the mercy of the Queen of Heaven, and they established a yearly feast in honor of the icon on February 17.

The Mother of God of Pruzhen, Poland.[11] One of the most significant events of our times occurred on April 9, 1934, in the St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in the city of Pruzhen. It was Easter Friday. Tears began to flow from the eyes of the Mother of God represented as standing beside Christ on the Cross. This extraordinary miracle was witnessed not only by Orthodox believers, but also by Catholics, sectarians, and even unbelievers. They all testified of this fact also before a special investigating committee sent by the bishop of the Polessk diocese. This committee, after a thorough investigation, acknowledged the indisputability of the miracle. News of the miracle spread rapidly through the whole diocese and the surrounding area. Pilgrimages were started. People flocked by the thousands to the wonderworking icon the whole summer of 1934, and church processions to the icon continued in the following years.

These examples of weeping icons in the history of the Orthodox Church permit an historical perspective of the contemporary weeping icons and allow one to make certain general statements about them. They are not new to Orthodox experience, but they have been extremely rare, and to very few has it been granted to sec the tears of the Mother of God more than once in a lifetime. Yet the response to them on the part of Orthodox believers is ever one and the same, coming as it docs from the Christian consciousness that is developed in one according to the depth of his participation in the life of the Church.

By Her tears the Mother of God shows Her nearness to men, Her concern for them, and the power and warmth of Her prayer for them. Her intercession for the human race becomes, as it were, visible in Her tears. Seeing this miraculous sign Orthodox Christians are themselves moved to fervent prayer, the response of the first witnesses of the weeping icons throughout the centuries has always been immediately to celebrate a service of prayer before them, and the icons become after this a center of pilgrimage.

But beside the general purpose of calling Christians to prayer, the weeping icons have almost invariably served a more specific function. They have been a sign to believers, sometimes of a single city, sometimes of a whole province or nation, of an impending misfortune affecting all, the rareness of the sign being an indication of the extraordinary character of the event it portends. The tears of the Mother of God are a kind of final warning of the impending catastrophe-which is always, as Orthodox Christians well know, sent by God as a chastisement for sin and a final call to sincere repentance and fervent prayer. The outcome is not always certain Often, indeed, the weeping icons have been followed by disaster; but occasionally, after great peril, disaster has been averted. Here, as in all God’s dealings with men, the freedom of man plays an important role; the fervency and depth of man s response to the heavenly tears help to determine whether the misfortune will be averted.

Of all the weeping icons, however, the new weeping icons of America are the most extraordinary. One weeping icon was followed by a second, and then by a third; and there have been tears, not for a day or a week, but—from the third icon—for over five years. If the weeping icons in general have been a sign to believers, these newest ones are unmistakably so. What precisely they portend no one, of course, can say; but whatever it is, it evidently concerns all Orthodox people in America, and perhaps the whole nation as well. Certainly there is much in America today that could call forth Divine chastisement. In many Orthodox Churches in America the departure from traditional Orthodox faith and practice has advanced so far as to make union with the apostate Church of Rome a logical next step, and indications are that this step will not be long in coming; multitudes of Orthodox believers relax the disciplined spiritual life prescribed by the Church in order to follow the increasingly self-indulgent example of the American populace; and this same populace gives no indication of seeing in its own still-free land a last bulwark against the soul-devouring monster of Communism, but rather abandons its last vestige of Christian conscience to lead a life inspired by indifference and atheism, thus hastening the advent of the universal atheist regime.

It is not America alone that has witnessed the tears of the Mother of God in our own day. In New Zealand a photograph of the Tikhvin Mother of God of Mt. Athos, which itself wept in 1877, began to weep in June, 1956 [12], and has continued to weep periodically since then; this icon was received in 1952 from a monk on the Holy Mountain. And in Greece, in the village of Ersova near Mt. Athos, at about the same time a lithograph icon of the Mother of God [13] wept for forty consecutive days such copious tears that they were collected in bottles. Perhaps these signs in distant continents arc related to the American weeping icons, and they all together portend some event of concern to the entire world. Some monks on Mt. Athos and elsewhere believe they refer to an event for which, as numerous other signs indicate, the world would seem at last to be ripe: the birth of Antichrist.

What is certain is that these tears of the Mother of God speak directly to the heart of every Orthodox believer, calling all to repentance, amendment of life, and a return to Orthodox faith and tradition in their fullness.

[1] Orthodox Russia, 1960 (nos. 6, 8, 16, 19)

[2] See, for example, Life, May 2, 1960; the New York Journal American, April 19, 1960, p. 8.

[3] St. Dimitri of Rostov, Lives of the Saints (Sept.).

[4] E. Poselyanin, The Mother of God

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Bp. Nikodim of Belgorod, Russian Podvizhniki of the 19th and 20th Centuries (July, p. 537; April, pp. 104-5)

[10] E. Poselyanin, The Mother of God

[11] Archpriest Nicholas Dombrovsky, in Orthodox Russia, 1950 (no. 10).

[12] Orthodox Russia, 1962 (no.4)

[13] Orthodox Russia, 1960 (no. 10).

by Saint Seraphim of Platina [†1982]

The Orthodox Word, Volume 1, No. 6, 1965, pp. 215-25

Pas de commentaire