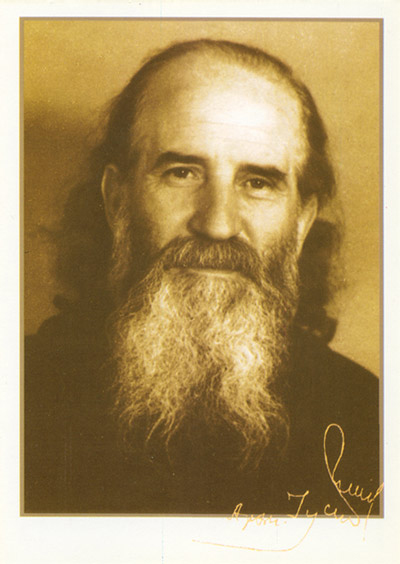

Commemorated. March 25 (†1979)

The mission of the Church is to make every one of her faithful, organically and in person, one with the Person of Christ.

—Fr. Justin Popovich [1]

With the words of the Archangel Gabriel, Rejoice, thou who art full of grace, the Lord is with thee [Luke 1 28] [2], the Lord chose to frame the life of our holy Father Justin. He was born at midnight on the feast of the Annunciation, March 25, 1894, and eighty-five years later he reposed on the same day. In that period, he ceaselessly proclaimed the good news of the Incarnation of the God-man Christ.

As a second Gabriel, he announced these tidings to a world grown weary with the wars and modernity of the twentieth century. With absolute conviction, Fr. Justin could personally bear testimony that “man learns the complete truth about man, about the purpose and meaning of his existence only through the God-man. Outside of Him a man turns into an apparition, into a scarecrow, into nonsense. Instead of a man you find the dregs of a man, the fragments of a man, the scraps of a man. Therefore, true manhood lies only in God-manhood; and no other manhood exists under heaven.” [3]

Fr. Justin was born in Vranjc, southern Serbia, and given the name Blagoje in honor of the day of his birth: the feast of the Annunciation [4]? His pious and God-fearing parents, Protopresbyter Spyridon and Protinica Anastasija Popovich, imbued him with reverence and piety from early childhood. Fr. Spyridon was the seventh generation of Popoviches to be ordained to the priesthood—the priestly rank being reflected even in the family name Popovich, “family or son of a priest.”

As a child, Blagoje and his parents often visited the Prohor Pchinjski Monastery, dedicated to St. Prohor the Miracle-worker. There, when he was still a young boy, he witnessed the miraculous healing of his mother from a deadly disease through the intercession of St. Prohor.

From elementary school, Blagoje was an excellent student, but his greatest love was for the Bible, and the four Gospels in particular. Even at this early age, Blagoje perceived that education without Christ was no true education. Later, he would write:

Let us ask what the goal of education is, if it is not the enlightening of man, the illumining of all his abysses and pits, the banishing of all darkness from him. How can man disperse the cosmic darkness that assails him from all sides, and how can he banish the darkness from his being without that one light, without God, without Christ? Even with all the light that is his, man without God is but a firefly in the endless darkness of this universe. His science, his philosophy, education, culture, technology and civilization are but tiny candles that he lights in the obscurity of earthly and cosmic events. What do all these tiny candles mean in the endless night and the darkness of individual, social, national and international problems and events? [5]

At the age of fourteen, Blagoje began reading the Bible in earnest, and throughout the rest of his life he always carried the New Testament with him, reading faithfully three chapters a day. His deep understanding of the mysteries of the Gospels through a life lived in them gave him the authority to instruct others in this occupation:

It is a book that must be read with life—by putting it into practice. One should first live it, and then understand it… Do it, so that you may understand it. This is the fundamental rule of Orthodox exegesis.[6]

In 1905 young Blagoje entered the nine-year program of secular and religious study at the Seminary and Faculty of St. Sava in Belgrade. At that time, entry into the seminary was extremely difficult. Out of the thousands of students who applied, only about one hundred were admitted. On all of his entry exams Blagoje received the grade of “Excellent,” and he maintained this academic standard for the rest of his seminary education.

The Belgrade Seminary was renowned as a holy place of asceticism and for its high standard of scholarship. Among its many excellent instructors, Bishop Nikolai (Velimirovich)—then a hieromonk—stood out as a beacon of sanctity and erudition. Fr. Nikolai was Blagoje’s spiritual father during his years as a seminarian and became, without a doubt, the single most influential person in his life. In later years Fr. Justin would refer to him as “the thirteenth apostle and the fifth evangelist.”

It was during this period that Blagoje came to love the works of Dostoevsky, whose works would be the subject of his thesis at Oxford. In his biography of Fr. Justin, Bishop Atanasije (Yevtich) writes:

Dostoevsky … was really his [Fr. Justin’s] unique “teacher and tormentor,” as he himself would say. And this was because they both encountered and collided with the same eternal problems, and only in Christ did both of them find, uncover, and experience the resolution of their tormenting questions and discover the only salvific way out of all the desperate situations and the tragedy of human life.

He also came to love St. John Chrysostom and his works at this time. It was a veneration that would continue throughout his life. In a journal entry for 1923 he wrote:

O dear father Chrysostom, every thought about thee is a feast for me, and a joy for me, and paradise, and rapture, and help, and healing, and resurrection… The holy Chrysostom is the eternal dawn of my soul and of the whole Orthodox Church. He is a most beloved intercessor; he is a most articulate God-given tongue of earth to heaven, through whom the earth conveys to heaven its sighs, its pains, its hopes, and its prayers.

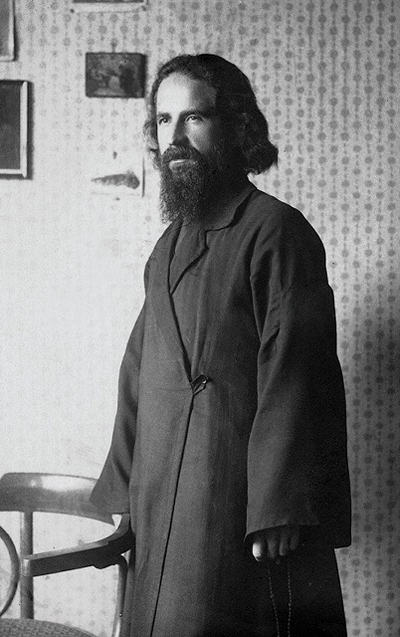

In 1914, at age twenty, Blagoje finished the nine-year program of St. Savas in Belgrade. His greatest desire now was to dedicate his life fully to Christ and take the monastic vows. His parents, however, were completely opposed to this, and petitioned both the bishop of Nish and Metropolitan Dimitrije [7] of Belgrade to forbid the tonsure.

Although his resolution remained firm, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 forced Blagoje to put aside his own desires in order to serve his country. In the autumn of 1914, Blagoje joined a student brigade of medical orderlies in Nish. At that time the entire country was occupied by the Austrians. The deprivations were great in that region, and Blagoje contracted typhus during the following winter and had to spend over a month in a hospital. On January’ 8, 1915, he resumed his duties and followed the retreating Serbian army into the Skadar region.

On the eve of the feast of St. Basil the Great, January 1, 1916, Blagoje received the monastic tonsure with the blessing of Metropolitan Dimitrije in the church in Skadar, taking the name Justin, after the great Christian philosopher and martyr for Christ, St. Justin the Philosopher (†166). According to his disciple, Metropolitan Amphilohije:

Fr. Justin was a philosopher in the true sense of the word. That is why he probably chose the name of Justin the Philosopher, a martyr, and strived all his life to emulate him, both in philosophy and martyrdom… However, his philosophy was not philosophy according to human understanding… In all of his works, in all of his prayers, in all of his sighs, in a word—with his entire life, Fr. Justin strove to sing, to express, to describe with words the indescribable image of Christ, to express his own volcanic love for the God-man Christ. [8]

Metropolitan Dimitrije then sent Fr. Justin and three of his fellow students to the St. Petersburg Seminary in Russia. These measures were taken to spare the lives of these talented young men, who would be of enormous need to the Serbian land after the war.

Arriving during the last days of Holy Russia before the revolution, the young and talented Fr. Justin was inspired by the deep piety of the Russian people and the spiritual inheritance they had received. Although his stay was short, his sojourn there influenced the rest of his life.

With the storm of the Bolshevik Revolution on the horizon, Fr. Justin was forced to leave Russia and, at the prompting of his spiritual father, Bishop Nikolai, prepared to study theology in Oxford, England. He spent seven semesters at Oxford—from November 1916 to May 1919. During this period he became intimately familiar with Western culture and Western man. According to Bishop Atanasije: “He did not oppose Western scholarship and science as such, as much as its unhealthy rationalism penetrated with sin, which demoralizes man, making him solipsistic, closing him up within himself, binding him only to this world and life.” And so, for his doctoral dissertation he turned to the works of Dostoevsky, in whom “he found only a confirmation of his own personal experience of man as Eastern Orthodoxy experiences man and as Western Christianity distorts man.” In the last chapter of his dissertation, “The Philosophy and Religion of Dostoevsky,” Fr. Justin entered into sharp criticism of Western humanism and anthropocentrism, especially that of Roman Catholicism. The English professors demanded from him a change of such views. This, however, was inconceivable for Fr. Justin, and thus he left Oxford without a diploma.

Western humanism and its effect on man would be a subject that Fr. Justin would return to throughout his life:

What is left of a man when the soul is removed from his body? A corpse. What is left of Europe when God is torn from its body? A corpse. With God banished from the cosmos, has it not become a corpse? What is a man who denies the soul within him and in the world around him? Nothing but molded clay, a walking coffin of clay. The result is devastating. Enamored of things, European man himself finally becomes a “thing.” Personality is devalued and destroyed. What is left is a man-thing. There is no whole, integrated, immortal and God-like man, but simply fragments of a man, a bodily husk from which the immortal spirit has been driven out. Although this husk is burnished and adorned, it is still a husk. European culture has deprived man of his soul; it has made him artificial and mechanical. It is like a monstrous machine that devours men and makes them into things. The end result is touchingly sad and movingly tragic: man, a soulless thing among soulless things. [9]

In May 1919 Fr. Justin returned to Serbia—now absorbed into the newly created Yugoslavia—to teach theology at the St. Sava Orthodox Seminary in Sremski Karlovci. Later that year Fr. Justin was sent to the Orthodox School of Theology in Athens to complete his doctoral work. This time his dissertation, “The Mystery of Personality and Knowledge According to St. Macarius of Egypt,” was successfully defended. Just as in Russia, Monk Justin traveled throughout the countryside of Greece, benefiting spiritually from the Orthodox Byzantine tradition.

In 1920 Fr. Justin was ordained a deacon. As his liturgical and ascetical life deepened, Fr. Justin matured spiritually and became known throughout Greece as a devout ascetic. Even while he was still in Oxford this transformation had already begun. A young Anglican monk who became a close acquaintance of his, observing his unceasing prayer and abundant tears, sincerely admitted one day, “I only now understand that the repentance and faith you have is something different from what we understand in the West and how we’ve been taught. Now I see that we in the West don’t know what repentance is.”

Deacon Justin returned to Sremski Karlovci and resumed his teaching duties at the Seminary in May 1921. Desiring to convey to the seminarians how Orthodox theology is lived, he called for the introduction of a course on the Lives of the Saints. With the establishment of this course, he began translating these Lives into modern Serbian for his students. This would be the impetus for Fr. Justin’s lifelong undertaking: to translate twelve volumes of the Lives of the Saints from the Greek, Slavonic, and Syriac sources. Published between 1972 and 1977, these texts amount to over seven thousand pages of writing. In his introduction to the twelve volumes, Fr. Justin eloquently writes of the importance of the saints in every Christians life:

The Lives of the Saints are nothing else but the life of the Lord Christ, repeated in every saint to a greater or lesser degree in this or that form. More precisely it is the life of the Lord Christ continued through the saints, the life of the incarnate God the Logos, the God-man Jesus Christ who became man. This was so that as man He could give and transmit to us His Divine life; so that as God by His life He could sanctify and make immortal and eternal our human life on earth. [10]

In addition to the Lives of the Saints, Fr. Justin lectured on the New Testament, Dogmatics, and Patristics. Prior to each lesson on the Scriptures he opened with this short prayer: “O Most Sweet Lord, by the power of Thy Holy Gospel and through Thine Apostles, teach me and announce through me what I am to say.”

In 1922 on the Feast of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, Fr. Justin was ordained a priest by His Holiness Patriarch Dimitrije. Throughout his ordination, Fr. Justin was in tears, crying as a newborn babe in the Lord. The date of his ordination was fitting, as his life would in many ways follow the path of the first evangelist and Christian confessor.

Fr. Justins fame as a man of prayer began to spread, and people from all walks of life came to him for Confession and counsel, including students, intellectuals, peasants, and members of his beloved Bogomoljak Pokret (Serbian Prayer Movement), originally formed and led by his spiritual father, Bishop Nikolai.

The zealous Fr. Justin was also in close contact at this time with two great Russian Orthodox pastors: Metropolitan Anthony Khrapovitsky, who taught at the Seminary in Sremski Karlovci, and St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco, at that time a hieromonk.

In 1922 Fr. Justin helped to found the Orthodox journal Christian Life, and the following year he would become its editor. In this journal appeared his first doctoral dissertation, “The Philosophy and Religion of Dostoevsky,” for which he had been censured at Oxford. Fr. Justin used his position as editor to call for the return of Serbs to a true Orthodox life in Christ. In issues ranging from the secularization of state schools to the innovations proposed at the Pan-Orthodox Congress at Constantinople, Fr. Justin was adamant in his position that man could only be a complete and whole man in the light of Christ the God-man.

Not everyone was pleased with Fr. Justins work as editor of Christian Life. Certain archpastors were stung by some of his writings and desired to bring him before the Holy Synod for trial, but the Patriarch freed him of this, replying that everything that Fr. Justin wrote was the truth.

In defense of himself and the articles he had published, Fr. Justin wrote in uncompromising terms, “There are some that are calling for reforms in the Church, not sensing that all reforms that are in the spirit of the times are pernicious for the Orthodox Church.”

In 1931 after briefly teaching at the seminary in Prizren, Fr. Justin accompanied Bishop Joseph (Cvijovich) to Czechoslovakia in order to reorganize the Church of the Carpatho-Russians. There he worked tirelessly, bringing back great numbers of Uniates to the Orthodox Faith. On his return, because of his success, he was offered a bishopric in a newly revived diocese in Czechoslovakia. In the end, he refused the offer and was instead sent to teach at the seminary in Bitol.

His experience in Czechoslovakia with the Uniates convinced him of the need for an exact and complete exposition of the Orthodox Faith in modern Serbian. As a result, he began writing his greatest work, The Orthodox Philosophy of Truth: The Dogmatics of the Orthodox Church, in three volumes. Volume one, published in late 1932, dealt with the sources and method of theology, the nature of God and the teaching on the Holy Trinity, creation, and divine providence. The success of this volume led to his appointment as professor of Holy Scripture, Dogmatics, and Comparative Theology at the Theological Faculty (Belgrade University). In 1935 the second volume, entitled The God-man and His Work: Christology and Soteriology was published. Fr. Justins Dogmatics became a standard textbook for seminaries not only in Yugoslavia but also in Greece, Bulgaria, and the United States. His knowledge of Hebrew, Syriac, Greek, Latin, Russian, Romanian, and many Western European languages, combined with his ascetical vision of life, produced for all Christians a magnificent analysis of the ancient Faith of the Church. The third and final volume, Ecclesiology: Teaching on the Church, was published many years later, in 1978.

In 1936 while a professor of the theological faculty, Fr. Justin had a vision of St. Seraphim of Sarov. The saint, wearing priestly vestments, approached him in a dream. Fr. Justin joyfully went to him, stretching out his hands and wanting to touch him, but St. Seraphim withdrew from him. “My soul was both joyful and sad at this. Joyful because I had seen him, and sad, because he had so quickly disappeared.”

In the late 1930s Fr. Justin turned his attention to missionary work among the Serbian intellectuals of Belgrade. He co-founded the Serbian Philosophical Society in 1938, and in the following two years published The Foundations of Theology and Dostoevsky on Europe and Slavism. Both of these works dealt with the nature and method of theology, and the problematic spirit and vision of Western civilization.

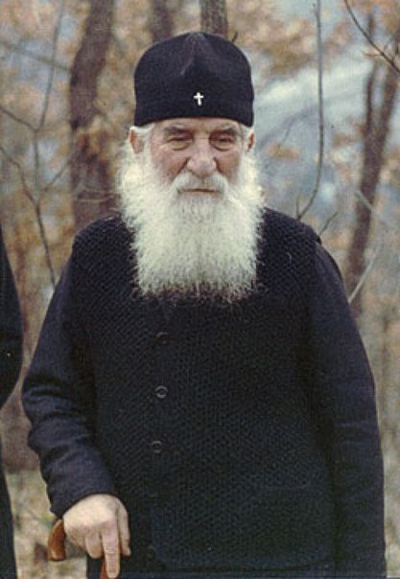

At the end of World War II, the newly installed Communist government forced Fr. Justin—a vocal anti-Communist—to leave his teaching position at Belgrade University. Fr. Justin’s influence on Serbian society, and especially the intellectuals, was in direct opposition to the plans of the atheist state. For two years after his exile from Belgrade, Fr. Justin moved from monastery to monastery in Serbia—to Kalenich, Ovchar, Sukovo, and Ravanica—and on May 14, 1948, he entered the Chelije-Archangel Michael Monastery in western Serbia.

When Fr. Justin arrived, the monastery was in shambles. There were only two habitable cells—one for Fr. Justin and the other for the few nuns who had been sent to reestablish monastic life in 1946. For both the nuns and Fr, Justin, life at Chelije was austere, characterized by poverty, prayer, and hard labor. They worked the arable land with bullocks, replanted the devastated forest, and with the help of the local people rebuilt the monastery. In addition to all the physical hardships, the Communist government kept Fr. Justin under constant surveillance as he continued to attract visitors from all over the Balkans and even the far corners of the world.

According to one of his spiritual children, he remained an ascetic until the time of his repose:

After dinner Fr. Justin would go to his workroom where he would read Holy Scripture, the Holy Fathers, and pray. He slept very little. He would get up very early and go to the monastery church to serve the Divine Services. Following this he would eat breakfast and return to his work—studying, translating and writing. When he grew old, he would rest for a short while after lunch and then return to his work. Every day would bring guests to see En Justin, who would find time to give them precious spiritual advice. When the evening arrived, he would return to the Church to serve, after which the holy mystery of Confession would be offered to all. [11]

For Fr. Justin the ascetic life was an integral part of his faith, and he called upon every Christian to follow this path:

Orthodoxy is ascetic effort and it is life, and it is thus by effort and by life that Orthodoxy’s mission is broadcast and accomplished. The development of asceticism—this ought to be the inward mission of our Church amongst our people. The parish must become an ascetic focal point. But this can only be achieved by an ascetic priest. Prayer and fasting, the Church-oriented life of the parish, a life of liturgy: Orthodoxy holds these as the primary ways of effecting rebirth in its people. The parish, the parish community, must be regenerated and in Christ-like and brotherly love must minister humbly to Him and to all people, meek and lowly and in a spirit of sacrifice and self-denial. And such service must be imbued and nourished by prayer and the liturgical life. This much is groundwork and indispensable. But to this end there exists one prerequisite: that our bishops, priests, and our monks become ascetics themselves. [12]

Fr. Justin would remain in Chelije Monastery to the end of his life. He was raised to the rank of archimandrite there, and was the spiritual head of the monastery. A school of iconography, renewing the Serbo— Byzantine style, was begun there, and a new chapel dedicated to St. John Chrysostom as well as residential quarters were constructed in 1970.

In addition to completing his monumental work, The Lives of the Saints, while at Chelije, Fr. Justin continued to produce an immense number of books and articles, including: Commentaries on all the Epis¬tles of St. Paul and St. John, Commentaries on the Gospels of Matthew and John, The Way of St. Sava as a Philosophy of Life (1953), The Lives of Sts. Sava and Simeon (1962), Man and the God-Man (1969, in Greek), The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism (1974), Three Divine Liturgies (1978), and The Divine-human Way (posthumously in 1980).

Despite Ft. Justin’s exile to a remote monastery, he remained a pillar of the Church, never afraid to call the faithful back to the Church’s true mission. He was unflagging in his condemnation of ecumenism, while at the same time he labored to heal the rift in the Serbian diaspora in North America, calling for forgiveness and repentance in order to create true reconciliation.

In 1977 Fr. Justins health began to fail, and at the end of March 1979 he prepared to enter eternity. Until the end he remained conscious. He was able to take leave of the entire monastery and his spiritual children, blessing each one. St. Justin reposed on. March 25, 1979, on his birthday, rhe Feast of the Annunciation. He was eighty-five years of age. A great multitude filled the small Chelijc Monastery for Fr. Justin’s funeral, including three bishops and hundreds of mourners from as far away as Greece, Crete, Germany and France. He was laid to rest facing east behind the main church of Chelije Monastery.

Fr. Justin left behind a powerful testimony of his life: the thousands of pages of his pastoral, dogmatic, hagiographical, and theological works—writings that were the fruit of a faith fervently lived. His words continue to inspire new generations, and his intercessions before the throne of God are evident to those who pray at his grave. May the time soon come when he will be formally listed among the saints.

Holy Father Justin, pray to God for us!

Sources:

Hieromonk Atanasije (Yevtich) [now retired Bishop of Herzegovina], “A Biography of Fr. Justin,” in A Collection of the Works of St. Justin (Popovich), vol. 1 (Moscow: Palomnik, 2004), pp. 9–54, in Russian.

Fr. Daniel Rogich, Serbian Patericon: Saints of the Serbian Orthodox Church, vol. 1 (Platina, Calif.: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 1994), pp. 247-60.

Hill, Elizabeth, “Obituary of Archimandrite Justin Popovich,” Sobornost, vol. 2, no. 1 (1980), pp. 73–79.

[1] “The Inward Mission of Our Church” in Orthodox Faith and Life in Christ (Belmonr, Mass.: Institute for Byzantine and Modem Greek Studies, 1994), p. 23.

[2] And in the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, To a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary. And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women. And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. Luke 1 26–30

[3] “The God-man: The Foundation of the Truth of Orthodoxy” in A Treasury of Serbian Orthodox Spirituality, vol. 4, The Struggle for Faith (Grayslake, Ill.: Serbian Orthodox Diocese of the United States of America and Canada, 1989), pp. 96–97

[4] Blagovest means Annunciation or Good News in Serbian.

[5] “Humanistic and Theanthropic Education” in The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism (Birmingham, England: Lazarica Press, 2000), p. 136.

[6] “How to Read the Bible and Why” in A Treasury of Serbian Orthodox Spirituality, vol. 4, The Struggle for Faith, p. 78.

[7] In 1920 Metropolitan Dimitrije would become the first Patriarch of the restored Patriarchal throne.

[8] Hieromonk Amphilohije (Radovich) [now Metropolitan of Montenegro], “Eulogy in Memory’ of Father Justin” in Orthodox Life, 1981, no. 2, p. 28.

[9] “Humanistic and Theanthropic Culture” in The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism, pp. 103-4.

[10] “Introduction to the Lives of the Saints” in Orthodox Faith and Life in Christ, p. 36.

[11] “Father Justin Popovich: The Hidden Conscience of Orthodox,” An Interview with Father Peter Milosevich, Divine Ascent, vol. 1, no. 1 (1997), pp. 42–43.

[12] “The Inward Mission of Our Church” in Orthodox Faith and Life in Christ, p. 30.

By Riassaphore-monk Adrian

The Orthodox Word, Vol. 43, No. 5, September-October, pp. 212-26

Pas de commentaire