In connection with the forthcoming 50th anniversary of the canonical establishment of the independence of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, free of Communist domination, we wish to present brief biographical sketches of the outstanding pillars of this Church. Some of them have attained unquestionable sanctity and shine today against the background of the present age of apostasy as indeed equal to the great Saint-Hierarchs of the truly Ecumenical Orthodox Church of Christ the Saviour. With some of these archpastors the readers of The Orthodox Word are already acquainted: Archbp. John Maximovitch (1966, no. 5), Metrop. Anastassy (1965, no. 4), Archbps. Ioasaph (1968, no. 2), Vitaly (1965, no.3), and now Theophan.

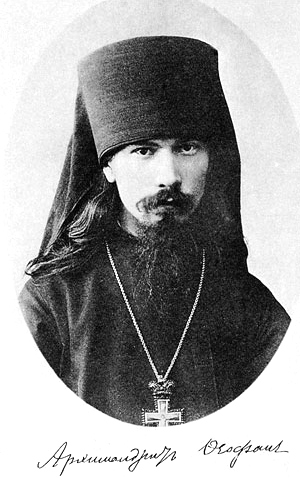

Born Basil Dimitrievich Bystrov in 1873, he was the son of a priest of the village of Podmosh in the diocese of St. Petersburg and a pupil of the local religious schools. In 1892, after finishing the course of instruction in the seminary, he entered the St. Petersburg Theological Academy first on the list of examinees. He went from year to year in the Academy as first student. In 1896 he completed the Academy and remained there to teach; in two years he became a hieromonk and in 1901 was raised to the rank of archimandrite and promoted to temporary inspector of the Academy. 1905 he was honored with the degree of Master of Theology for his work, “The Tetragrammaton, or the Divine Name of Jehovah in the Old Testament,” and three years later named director of the Academy. That same year in the St. Alexander Nevsky Lavra he was consecrated Bishop of Yamburg, the fourth vicar of the St. Petersburg Diocese. On the eve of his consecration as bishop, in his sermon addressed to his consecrator-hierarchs, he testified:

“…Ever since I came into being, I observe in myself an unceasing battle of life and death in the realm of existence, both natural and spiritual. O, how heavy this battle has been at times in me; but may there be thanks to the Lord for it! It has deeply implanted in my heart the saving truth that I in myself am nothing, and that the Lord for me is everything.”

Interiorly he was of a highly spiritual cast of soul and a great man of prayer, for which he became widely known preeminently in the capital society. At one time he became the spiritual advisor to the Imperial Family. Later, he would recall with emotion how he often celebrated the Liturgy at the Court church on weekdays and how the Empress herself and all four Great Princesses sang on the cliros. The Revolution overtook him as Archbishop of Poltava, from whence he emigrated with the White Army through Constantinople to Bulgaria, where he lived many years.

Regarding the height of his spiritual life one may see from the memoirs of H. Y. Kontzevich:

“I was told that in his student years he had labored intensely in asceticism, slept on the floor and the like, and ruined his health; he had tuberculosis and poor digestion. Therefore in his mature years he was an opponent of excessive physical asceticism. His voice always remained very weak. He was of small stature, thin, and there was something special in him that evoked a feeling of reverent awe. Jokes or laughter in his presence were impossible. He was like an unearthly being, a manifestation from the other world. The practical problems of life were foreign to him. He was a very learned man. To govern a diocese and look into worldly affairs were not his calling. It was a great mistake to deprive him of the rectorship of St. Petersburg Academy, where he was in his place. He was a great expert in patrology and patristics. He himself being a practicer of mental prayer and having attained a high stage in this practice, he knew as no one else the teaching of the Holy Fathers concerning this “science of sciences.” Archpriest Sergy Chetverikov, who wrote together with Abbot Chariton of Valaam Monastery a book on the Prayer of Jesus,[1] asked to be a disciple of Archbishop Theophan. But he was given a condition by the holy man: break off with the YMCA.[2] This Fr. Sergy would not do.

“My husband went to college in Poltava and knew how the people there revered Vladika Theophan. When he came to serve in the cathedral, the steps of the temple and the whole path by the entrance were strewn with flowers. My aunt, E. A. N., went with her husband to Poltava and after returning related to me the following incident: In Poltava there lived an especially devout couple. They were exceptionally devoted to Vladika. When the husband died, the widow, being in great grief, asked Vladika if he could inform her concerning the lot of her husband beyond the grave. Vladika answered that in a short time he might be able to give her an answer to her question. A certain time passed and Vladika, who had prayed, told the widow that her husband had found mercy with God.

‘Another incident was related by Vladimir Davidovich, Prince Zhevakhov, who later became Bishop Ioasaph. He asked Vladika Theophan concerning the lot of the bishop of Belgorod, who had been found hanged in the bathroom of the episcopal residence. Had his soul perished? Vladika Theophan said that this bishop had not perished. He had not hanged himself, but this had been done to him by demons. It turned out that this house had been rebuilt, and earlier there had been a house church there. But the builders had blasphemously made a bathroom where previously there had been the sanctuary and had stood the altar. When consecrated places are defiled, or where murder or suicide have been performed, and the grace of God has left the place, there demons settle in. Whether or not this bishop had been to blame in this blasphemous act, he turned out to be a victim of it.

“When Vladika lived in seclusion in Clamart, near Paris, I had the honor of sometimes being present when he served the Divine Liturgy, and afterwards of sharing his trapeza at his table, when he would have talks on spiritual life, illustrating them by living examples of holy ascetics. With difficulty, being already then a little deaf, I devoured with strained attention his priceless narratives, as if coming from the otherworld. Later, when I was informed of his death, an unexplainable torrent of bitterness seized me; I wept, knowing that a real saint had left this earth, leaving spiritual emptiness behind him and making this world gray and dull. At that time I had a terrible and unceasing toothache which gave me no peace. In agony, a flash of hope enlightened me: I turned mentally to Vladika as if he were alive right here and could hear me, and I prayed to him for help. Instantly the pain stopped! Although I never doubted his sanctity, this miraculous intercession was to me a clear sign of his being indeed a saint of God!”

Not without interest are his words concerning the future of much-suffering Russia, written in a letter to the same person in 1925:

You ask me about the near future and about the last times. I do not speak on my own, but give the revelation of the startsi. And they have handed down to me the following: The coming of Antichrist draws nigh and is very near. The time separating us from him should be counted a matter of years, and at most a matter of some decades. But before the coming of Antichrist Russia must yet be restored, to be sure, for a short time. And in Russia there must be a Tsar, fore-chosen by the Lord Himself. He will be a man of burning faith, great mind and iron will. This much has been revealed about him. We shall await the fulfillment of what has been revealed. Judging by many signs, it is drawing nigh, unless because of our sins the Lord God shall revoke, shall alter what has been promised. According to the witness of the Word of God, this also happens.

Memorable also was the moment when Archbishop Theophan met with a group of clergy of the “living church” trend and some liberal professors at the Moscow All Russian Council in 1917–1918. Between adherents of the Church order of Holy Russia and modernist clerics the dispute never died out during the whole time of work on the Council as to whether one should conduct church life by the old course or make concessions to the spirit of the times and modernize church life. And here the modernists politely, respectfully came to Archbishop Theophan; apparently even they felt in him a spiritual giant of Orthodoxy… “We respect you, Vladika, we know your church wisdom… But the waves of the times flow swiftly, changing everything, changing us; one must give in to them. You, too, must give in, Vladika, to the raging waves… Otherwise with whom will you be left? You will be left alone.”

“With whom will I be left?” Vladika meekly answered them. “I will be with St. Vladimir the enlightener of Russia. With Sts. Anthony and Theodosius the Wonderworkers of Kiev-Caves Monastery, with the holy Hierarchs and Wonderworkers of Moscow. With Sts. Sergius and Seraphim and with all the holy martyrs, God-pleasing monks and wonderworkers who have gloriously shone forth on Russian soil. But you, dear brothers, with whom will you be left if even with your great numbers you give over to the will of the waves of the times? They have already carried you to the flabbiness of Kerensky, and soon they will carry you under the yoke of the brutal Lenin, into the claws of the red beast.”

The church modernists left Vladika in silence after his reply. (Maharoblidze.)

The last years of his secluded life be spent in France; he went into retirement and lived as a hermit in the country in certain caves. Concerning the conditions of the last years of the life of Archbishop Theophan, the “Hierarch-Cavedweller,” Fr. Theodore I. relates:

“Vladika died in the years of the German occupation, in the village of Amboise in France. Here we visited his modest grave in the small Catholic village cemetery, on a hill. The nearest settlement to the cemetery, with an old Catholic church, is half a mile. How quiet it was at the cemetery! There was an Orthodox cross, name, dates. We served a panikhida with two old women, his servants-novices, perhaps nuns in secret tonsure. We went home quietly. The road was about two or three miles to the place where, in chalk caves in the hills, the hierarch lived.

“There were three rather long, high, well-carved-out caves. Perhaps this reminded him of the life of St. Paul of Thebes and St. Anthony the Great. In one was the former cell of Vladika, which was also his house church. In another lived twelve fierce dogs—doberman-pincers, capable of tearing a man apart in a minute. During the day they were chained. In the third cave lived goats, geese, and ducks, which comprised the whole of Vladika’s farm. In a fourth cave was the storehouse, where on the floor we saw a sack of walnuts, furniture piled high, beds, tables, etc.; there we lodged for the night. In the garden there was a well and some fruit trees, and on the hill a vineyard. There was home-made strong and aromatic wine, and well-churned butter, milk, cheese, etc., which were for sale.

“In Vladika’s cell we saw two of his photographic portraits; a Bible with dry flowers inserted, gathered at St. Seraphim’s canal at Diveyevo, and other sacred things put in; a case with relics, perhaps as many as 24, in little gold vessels; and much else of sacred relics…” Such was the atmosphere of his last earthly dwelling place.

After his holy repose, exactly on the 40th day, the righteous Vladika appeared to his grieving spiritual son, Ioasaph, later Archbishop of Canada, concerning which this marvellous ascetic-enlightener of Canada[3] related the following, which is a testimony of Vladika Theophan’s sanctity:

“After the death of my marvellous preceptor, I grieved terribly… It was very difficult for me, and I prayed much for him… And then, on the night of the 40th day after his repose, I dreamed I was standing before a magnificent church, from which after the service a multitude of hierarchs came out. I recognized the great hierarchs—Sts. Basil the Great, John Chrysostom, Gregory the Theologian and many others; suddenly in their midst I saw—Vladika Theophan! I ran up to him: “Vladika, where do you come from?” “Well, as you see, we have just served Liturgy together. Come with us.” I went. All took places in a spacious automobile, or perhaps boat, which began as it were to sail in the air. Past us went hills, forests, valleys of indescribable beauty, wondrous churches and monasteries. My Abba began to point out these abodes to me and revealed their fates: “This one here will be saved, but that one, there below in the valley, will perish.”—It was terrible to behold! And all around us were beautiful gardens, and a wondrous fragrance. I looked with delight, without seeing enough… For a long time we were carried thus in the air, in the midst of this magnificence. Finally I could not contain myself and asked: “But where are we?” Vladika Theophan answered me: “And why is it you don’t understand—in paradise!” From that moment I was reassured, having understood that my dear preceptor had been found worthy of eternal blessedness.”

May the Lord grant to us also, by the prayers of the righteous Vladika Theophan, to be worthy of mercy with God. Amen.

[1] Translated as The Art of Prayer, Faber & Faber, London, 1966. Reviewed in The Orthodox Word, 1967, no. 2, p. 66.

[2] A pseudo-Christian organization that, especially in Europe, has worked hard to undermine the traditional Orthodox other-worldly spirituality and replace it with a purely humanitarian world-view. See The Orthodox Word, 1969, no. 4, pp. 146, 148.

[3] See The Orthodox Word, 1968, no. 2, pp. 88ff.

The Orthodox Word, 1969, Vol. 5, No. 5 (28), September-October, p. 191-96

Pas de commentaire