Report to the Synod of Bishops, 1952

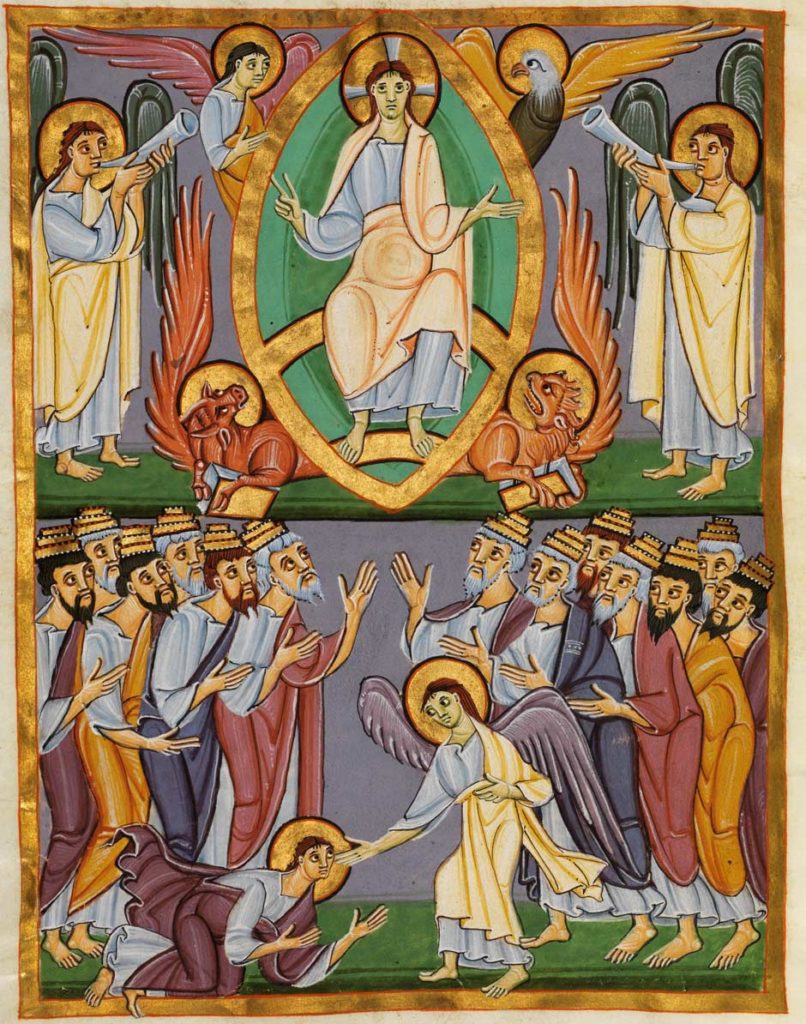

Establishing the boundaries of nations according to the number of Your angels, and gathering Your Church from among the scattered sons of Adam, multiplying Your saints in it like stars in the heavens, shining in the East and West, North and South.

Only a very small number of them have had church hymns composed for them, and their memory is celebrated throughout the Church. Countless others are known and especially venerated only in certain places, while in others they are partially mentioned through narratives of their lives and menologions, which list the days of their commemoration. Menologions, which began to be compiled from the middle of the last millennium, were largely composed by individuals on their own initiative, and their significance depended on the Church’s trust in and acceptance of their author. Much later, the Chetyi Menaion [Четьи Минеи], collections of the lives of saints, began to be compiled. The Russian people revered God’s saints both those who shone in their native land and those whom they knew from their lives. Both the calendars and the lives of the saints were repeatedly corrected and supplemented in Russia on the basis of newly collected data. The basis for the current Russian collections of the lives of saints is the Chetyi Minei of St. Dimitry of Rostov, which is one of his major works. Subsequently, with additions, they were published by the Holy Synod in Russian. The lives of the ancient saints also mention saints who are not commemorated today and whose lives are almost unknown. The most complete monthly calendar in Russia was compiled by Archbishop Sergius of Vladimir, including many saints of the East and West. No matter how extensive the knowledge of saints who shone outside Russia was in Russia, when the Russians made their great exodus from their homeland, it turned out that there were still many saints in other countries outside Russia, unknown even to careful researchers of lives based on the lives and calendars available to them.

Even in countries closest to Russia in terms of location, spirit, and blood, there were saints unknown in Russia who had a direct connection to it through their works and lives. Such were the disciples of the holy first teachers of the Slavs, Cyril and Methodius—the miracle worker Naum, Saint Clement, and others who helped with their guidance in translating liturgical books into the Slavic language; Saints John the Russian and Pachomius, natives of Little Russia, who were taken captive by the turks in the 18th century and are venerated in the Greek Church, but are unknown in Russia, although they belong to the Russian saints. In addition to them, there are many ancient and modern ascetics in Eastern countries who are still unknown in other regions. Since those countries are Orthodox and the saints are glorified by the Orthodox Churches, there could be no hesitation or doubt in venerating those saints on a par with the saints already known in Russia. Together with the inhabitants of those countries—Greece, Serbia and Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Romania—all Orthodox Christians should resort to them and venerate them.

The situation in the West was more complicated. Christianity was preached here in the early centuries, in many places by the apostles themselves. For many centuries, Orthodoxy stood firm, and Eastern confessors even flocked here to seek support during times of heresy (Saints Athanasius and Maximus). Many martyrs and ascetics shone here, strengthening the Church. But at the same time, the departure and fall of the West from the one Universal Church obscured the truth here and mixed it with deception. It was necessary to establish which of those revered here as pillars and saints of the faith were truly such. This could not be left to private researchers; it was the responsibility of the diocese, and it had to be done. The decisions of the Council of Russian bishops on the veneration of Western saints are by no means their canonization, but rather a determination that the ascetic in question was venerated as a saint before the West fell away and [he] is a saint venerated by the Orthodox Church.

The absence of hymns and information about a saint in the East does not mean that his holiness is not recognized. After all, not all saints who are venerated in the East and who have shone there have church services composed for them. Almost every day in the Synaxarion and Prologue, the memories of saints are indicated, not only those to whom the service of that day is dedicated, but also others. Many saints do not have a specific day of remembrance, although they are mentioned in some services, for example, in the Service to the Saints who Shone Forth in Fasting, or they are already known and revered. The lives of martyrs, ascetics, and other saints are known only to God. All of them are glorified together on All Saints’ Day, as stated in the Synaxarion for that day. Saints who are unknown to this day in the East but are venerated in the West belong in their earthly lives to various centuries and achieved glory in various ways.

These are the martyrs of the early centuries, ascetics, and saints. The latter two categories are somewhat overlapping, as many of the ascetics later became bishops. There is no doubt about the former, that is, the martyrs. By their sufferings for Christ, they are as much martyrs as others venerated by the Church, some of whom are even included in verified Russian calendars; and now they are mentioned only because they are unknown to most lay people, who use only brief calendars and almanacs. Such are, for example, St. Pothinus, Bishop of Lyon, and the other martyrs of Lyon. It was necessary to point out to those now living near the places of their exploits and the remains of their holy relics these priceless spiritual treasures and to call on the Orthodox flock to venerate them. The West is full of such martyrs. Even in the first decades of our exile, private pilgrimages to local shrines began, but many are still unknown to this day, although other sights are well known.

The martyr Victor, who suffered alongside his converted guards Alexander, Felician, and Longinus, has been highly revered in Marseille since ancient times. St. Cassian the Roman built a monastery above their tombs, where he lived and died. The Orthodox calendar of saints includes several martyrs with the same name, Victor, but from the descriptions of their sufferings it is clear that they are different martyrs.

Another martyr who has been venerated since ancient times is St. Alban, who lived near London; his relics rest there to this day, and a detailed description of his deeds has been preserved. Some church monuments mention the legion of St. Mauritius, who suffered for Christ in the mountains of Switzerland, similar to the company of Saint Andrew Stratelates in the East; this Mauritius is named after another Mauritius, who suffered with his son Photios, but the place and nature of their sufferings show that they are different martyrs.

Bishop Saturnin, who was dragged through the streets of Toulouse for Christ in the middle of the third century, also consecrated Toulouse with his blood.

All of these are martyrs whose blood was the seed of Christ, whom the Church sings about almost daily in various “martyr” troparia and stichera, and who are also commemorated where the seeds of their blood flourished and bore fruit. They are [those] “by their blood,” « who throughout the world, as with purple and linen, adorned the Church[1]. The successors of the martyrs in the establishment of faith and piety in the West, as in the East, were saints and venerable ones. The first monasticism in the West is closely connected with the East. Information about it and its founders has been preserved in the works of their disciples or other writers close to them in time.

One of the main centers of [holiness] in the West was the Lerins Monastery. The life of its founder, St. Honoratus, has been preserved in a panegyric written by his disciple Hilarius, bishop of Arles. From it we learn that St. Honoratus traveled with his brother through Egypt and Palestine, and upon his return founded his monastery in Lérins. During his lifetime, he performed a number of miracles. St. Paulinus of Nola was spiritually connected with the monastery, and it was on his recommendation that St. Eucherius came there, leaving behind a number of his works, including “The Life of St. Mauritius and the Holy Martyrs of the Theban Legion,” which was mentioned earlier. St. Cassian lived in the monastery for some time and later founded his own monastery in Marseille. It should be noted that St. Cassian, venerated by the entire Orthodox Church, although his memory is celebrated only once every four years, in the Catholic Church he is considered a locally venerated saint, and his memory is celebrated annually only in Marseille, where the remains of his relics, preserved during their destruction during the French Revolution, rest in the Church of the Holy Martyr Victor. The same monastery was home to St. Vincent of Lerins, who is venerated even more in the East than in the West, a teacher of the Church who died around 450 and left behind his work on Sacred Tradition. England and Ireland are also connected to the East through the Lerins monastery, as it was a spiritual support for St. Augustine, who enlightened England, and his companions; St. Patrick, the enlightener of Ireland, also lived there for some time.

The monastery founded by St. Columba in Ireland maintained relations and communication with Eastern monasteries in the 11th century and, according to available data, even for some time after the fall of Rome and the break between Rome and the East. The remains of that monastery, with the relics of its venerable founder, still exist today, and a pilgrimage was recently made there, leaving a deep impression on its participants, as did the detailed life of St. Columba. The followers of St. Columba were the venerable Columbanus, Fridolin, and Gall, who came from Ireland to Switzerland in the 7th century and served in Gaul and Northern Italy to establish Christianity there and defend Orthodoxy from heretics. During their lifetime, they performed miracles and predicted the future. Detailed accounts of their lives were kept in local monasteries, and their memory is honored in places associated with them to this day.

Among the French saints, St. Genevieve and St. Cloud stand out. Saint Genevieve, born in 423 and died in 512, was distinguished from childhood by her piety and spent her entire life in prayer and extreme abstinence. As a child, her calling was foreseen by Saint Germanus of Auxerre, who blessed her to devote herself to God. She was spiritually connected with St. Simeon Stylites, who knew about her. She performed many miracles during her lifetime, among which the salvation of Paris from Attila through her prayers is particularly famous. The memory of that miracle is not only preserved in legend, but also marked by a column erected at the place where Attila reached. She is considered the patroness of Paris and France, and neither the destruction of her relics during the revolution nor the struggle against the faith could stop this veneration.

The Reverend Cloud was born into a royal family that perished during civil strife. Growing up and realizing the futility of earthly glory, he did not want to assert his rights, took monastic vows, and led a life of strict asceticism. For some time he lived in complete seclusion, then he founded a monastery, whose church still houses his relics to this day. He passed away in the middle of the 6th century.

The grandmother of the Reverend Cloud was Saint Clotilde, Queen of France, who raised her grandson. She is as important to France as Saint Olga is to Russia, Saint Ludmila to Bohemia, and Saint Helena to the Roman Empire. Thanks to her, her husband Clovis I was baptized and then finally established himself in Orthodoxy. Through her life, teachings, and prayers, she preached and established Christianity in France. After her husband’s death, she lived a life of abstinence and cared for those in distress. Warned from above of her death thirty days in advance, she passed away peacefully on June 3, 533. Her relics were preserved and carried in a procession until the French Revolution, when they were burned, and [now] only fragments of them remain.

The establishment of Christianity in France, preached there since the days of the apostles, was greatly aided by the saints of subsequent centuries, who simultaneously fought against the heresies that were spreading there. Saint Martin, Bishop of Tours, became particularly famous. His life is recorded in the Russian Chetya Mineya, although it is placed on October 12, not November 11, when he passed away and when his memory is celebrated. His teacher was the universally revered St. Hilary of Poitiers.

St. Martin, whose memory is widely revered, served to enlighten not only Gaul, but also Ireland, since St. Patrick, its enlightener, was his close relative and was under his spiritual influence.

St. Patrick was distinguished by his very strict life and, like St. Martin, combined his holy works with monastic feats. During his lifetime, he became famous for many miracles that contributed to the conversion of the Irish. He has been venerated as a saint since his death in 491 or 492, which was preceded by a series of signs testifying to his holiness. His contemporaries, who also laboured in Ireland, where they came to fight Pelagianism, were two pillars of the Church in Gaul, Saints Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes. Both were renowned for their fearlessness in preaching and protecting their flock from barbarians, as well as for the many miracles they performed during their lives and after their deaths.

St. Germanus of Auxerre passed away in 439, and his relics remained incorrupt for centuries until they were destroyed by the Calvinists. St. Lupus, mentioned in the “Iliotropion” by St. John, Archbishop of Chernigov [later Metropolitan of Tobolsk], took monastic vows at the Lerins Monastery, where he labored under the guidance of St. Honoratus, the founder of that monastery. St. Honoratus subsequently became Bishop of Arles, where St. Trophimus, a disciple of St. Paul, founded a church and served as its first bishop. St. Lupus was elected bishop of the city of Troyes, but continued to lead a strictly ascetic lifestyle. After saving his city from Attila and performing a series of miracles, he died in 479. His relics were preserved until the French Revolution, when they were burned, and [now] only small parts of them remain.

A century later, St. Germanus, Bishop of Paris, lived. His life story has been preserved from ancient times, showing that he was distinguished by his piety from early childhood, which was very difficult for him. Having taken monastic vows at the monastery of St. Symphorian, he led a very austere life, devoting a significant part of his time to prayer. Having become famous for his miracles, he later became bishop of Paris, where he continued his former way of life, combining it with pastoral and charitable works. Forewarned in his old age of his death, he passed away on May 28, 576. His relics were preserved for a long time, but their current location has not been established. A church that still exists today, begun under his care on the site of the temple of Isis in honor of St. Vincent the Martyr, bears his name. He also built a church in honor of St. Germanus of Auxerre, whom he greatly revered and emulated. His activities and life finally established Christianity in France.

A whole host of saints and ascetics shone forth in this country, pillars of Orthodoxy and teachers of piety. Later, the enlightenment of Northeastern Europe with Christianity began. The episcopal works of Saint Ansgar, Bishop of Hamburg and later of Bremen, are associated with this.

The life of Saint Ansgar was described by his disciple, Archbishop Rimbert, and has survived to this day. From it we learn that he was born in 801. At the age of seven, he had a vision calling him to serve God. Raised in a monastery, he was tonsured at the age of 12. His visions prompted him to lead a strict ascetic life and then to go and preach to the pagans living in Northern Europe. Starting at the age of 21 in Hamburg, he then moved to Denmark, where he baptized the king and his people. From there he went to Sweden. In 831, he was consecrated bishop of Hamburg and all the peoples of the North. His preaching extended to Sweden, Denmark, and the Polabian Slavs (present-day northern Germany). He was full of zeal and ready to suffer for Christ. Grieving that he had not received the martyr’s crown, he was comforted by a voice from above and peacefully departed to the Lord on February 3, 865. He combined his apostolic labors with inner self-improvement and sometimes withdrew into solitude. He was full of mercy, extending it wherever he learned of need, without limiting himself to any particular place. He was especially concerned for displaced people, widows, and orphans.

During his lifetime, St. Ansgar performed many healings, but in his humility he considered himself a sinner. He tried to do good deeds and miracles in secret. But God’s grace rested upon him so obviously, and his veneration was so great, that two years after his death he was already counted among the saints, and his name appears in the Martyrologies of 870. His incorruptible relics were kept in Hamburg until the Reformation, when they were buried, and only a part of them has survived to this day. His life and the power of God’s grace manifested through him, as well as his canonization as a saint when the West was still part of the Universal Orthodox Church, leave no doubt that he is a holy man of God. Archbishop Alexander collected all the information about him available in German, from both Catholic and Protestant sources, and all of it confirms everything stated here about St. Ansgar, describing the works of this great man in meekness and virtue, as well as his miracles. We also received a detailed biography in Danish. However, in view of the objections raised by one of our colleagues, it should be noted that they are unfounded. First of all, there is no evidence to suggest that St. Ansgar was a tool in the hands of the Roman See to assert its dominion and a conduit for the ideas that led to the separation from Rome. All efforts to find any references in the available sources have yielded no confirmation; on the contrary, they lead to the opposite conclusion, for today’s Catholics would not hesitate to exploit and glorify St. Ansgar, if such a thing had existed.

The holiness of St. Ansgar cannot be questioned because his name is not found in the Greek calendar or liturgical books, and this in no way implies that it is denied by the Eastern Church. The Greek calendars and liturgical books did not and still do not include St. Ansgar’s contemporaries, Sts. Cyril and Methodius, although they were well known in Constantinople. And the Catholic Church commemorates them more than St. Ansgar. Greek books do not mention St. Boris-Michael, the enlightener of Bulgaria, who was baptized by the Greeks, nor St. Ludmila of Bohemia, baptized by St. Methodius, nor St. Vyacheslav. There is no mention of St. Vladimir, nor of the saints Boris and Gleb, Peter of Moscow, who were glorified with the blessing of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Of all the Russian saints, only St. John of Novgorod and St. Barlaam of Khutyn are mentioned in the Greek Synaxaria, without a service dedicated to them. The Church of Greece commemorates the blessed Princess Olga, who has different troparia and kondakia there than we do. However, this does not mean that we should not honor the saints glorified in the Russian land, nor does it indicate their rejection by the Greeks. There are also many Greek saints whose names are found in the Menologia and monthly calendars, but they are commemorated locally, and services are performed there. Saint Ansgar served not political ends, but Christ, and the seal of his apostolate is the countries he brought to Christ. Their later apostasy does not diminish his service, just as the apostasy of Moravia and Pannonia for many centuries does not diminish that of St. Methodius. In various places across the universe, the righteous of Christ labored for the One God, were guided by the One Spirit, and were collectively glorified by Him. The wave of revolution and reformation destroyed their relics in the West, just as, having reached our Fatherland, it blasphemously touched Russian holy sites. It attempted to obliterate their memory, just as Julian the Apostate burned the holy relics of the saints. But they rejoice in the Heavenly Church, and we must glorify their labors even more, thereby glorifying God, who works miracles through them.

Decree on the veneration of ancient saints of the West

Decree No. 223, April 23, 1953

Living in the diaspora in countries where holy men and women, venerated by the Orthodox Church of Christ since ancient times, once lived and became famous for their sufferings or other feats, it is fitting for us to honor them and turn to them, without at the same time losing our devotion to the holy men and women of God to whom we have resorted in prayer before. In various places in ancient Gaul, now France, and other countries of Western Europe, the sacred remains of the martyrs of the first centuries and subsequent centuries, who were confessors of the Orthodox faith, have been preserved to this day. We call upon the clergy to commemorate during divine services—in litanies and other prayers—the saints who are the patrons of the place or country where the service is held, and those who are especially venerated, also during the liturgy. In particular, within the boundaries of Paris, it is appropriate to commemorate the holy martyr Denis, the venerable Genevieve, and also the venerable Clotilde; in Lyon, the holy martyr Irenaeus; in Marseille – the martyr Victor and the venerable Cassian, within Toulouse – the holy martyr Saturnin, bishop of Toulouse, in Tours – Saint Martin. In cases of uncertainty or confusion, please contact us for clarification and guidance. The flock should be encouraged to honor these saints.

[1] Adorned in the blood of Your Martyrs throughout all the world, / as if clothed in purple and linen, / through them Your Church cries out to You, O Christ God: / “Bestow Your bounties upon Your people, / grant peace to Your habitation, and great mercy to our souls.”

Synaxis of All Saints – Troparion — Tone 4

О почитании святых, просиявших на Западе

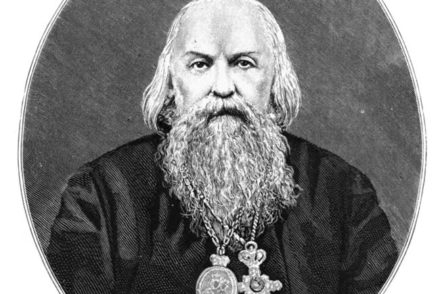

Владыка Иоанн — святитель Русского зарубежья / Сост. Прот. Петра Перекрестова. — М.: Изд-во Сретенского монастыря, 2008 – p. 416 – 27

Vladyka Ioann – Saint of the Russian Diaspora, Compiled by Prot. Peter Perekrestov. – 4th ed. – Moscow: Sretensky Monastery Publishing House, 2014, pp. 416-27

Translation: The Orthodox Pilgrim

Pas de commentaire