The 20th Century Orthodox Christian will find little that is strange in the Christianity of 6th century Gaul; in fact, if he himself has entered deeply into the piety and spirit of Orthodoxy as it has come down even to our days, he will find himself very much at home in the Christian world of St. Gregory of Tours.

The externals of Christian worship—church structures and decoration, iconography, vestments, services—after centuries of development, had attained essentially the form they retain today in the Orthodox Church. In the West, especially after the final Schism of the Church of Rome in 1054, all these things changed. The more tradition-minded East, by the very fact that it has changed so little over the centuries even in outward forms, is naturally much closer to the early Christian West than is the Catholic-Protestant West of recent centuries, which had departed far from its Orthodox roots even before the present-day” post-Christian” era arrived.

Some historians of this period, such as O. M. Dalton in the Introduction to his translation of St. Gregory’s History of the Franks (Oxford, 1927, two volumes (I & II)), find much in Christian Gaul that is ’Eastern” in form. This observation is true as far as it goes, but it is made from a modern Western perspective that is not quite precise. A more precise formulation of this observation would be the following:

In the 6th century there was one common Christianity, identical in dogma and spirit in East and West, with some differences in form which, at this early period, were no more than minor and incidental. The whole Church met together in councils, both before and after this century, to decide disputed dogmatic questions and confess the one true Faith. There were numerous pilgrims and travellers, especially “Westerners” going to the East, but also “Easterners” going to the West, and they did not find each other strangers, or the Christian faith or piety or customs of the distant land alien to what they knew at home. The local differences amounted to no more than exist today between the Orthodox Christians of Russia and Greece.

The estrangement between East and West belongs to future centuries. It becomes painfully manifest (although there were signs of it before this) only with the age of the Crusades (1096 and later), and the reason for it is to be found in a striking spiritual, psychological and cultural change which occurred in the West precisely at the time of the Schism. Concerning this a noted Roman Catholic scholar, Yves Congar, has perceptively remarked: “A Christian of the fourth or fifth century would have felt less bewildered by the forms of piety current in the 11th century than would his counterpart of the 11th century in the forms of the 12th. The great break occurred in the transition period from the one to the other century. This change took place only in the West where, sometime between the end of the 11th and the end of the 12th century, everything was somehow transformed. This profound alteration of view did not take place in the East, where, in some respects, Christian matters are still today what they were then—and what they were in the West before the end of the 11th century.” (Yves Congar, O.P., After Nine Hundred Years, Fordham University Press, 1959, p. 39, where he is actually paraphrasing Dom A. Wilmart.)

One might cite numerous manifestations of this remarkable change in the West: the beginnings of Scholasticism or the academic-analytical approach to knowledge as opposed to the traditional-synthetic approach of Orthodoxy; the beginning of the “age of romance”, when fables and legends were introduced into Christian texts; the new naturalism in art (Giotto) which destroyed iconography; the new “personal” concept of sanctity (Francis of Assisi), unacceptable to Orthodoxy, which gave rise to later Western “mysticism” and eventually to the innumerable sects and pseudo-religious movements of modern times; and so forth. The cause of this change is something that cannot be evident to a Roman Catholic scholar: it is the loss of grace which follows on separation from the Church of Christ and which puts one at the mercy of the “spirit of the times” and of purely logical and human ways of life and thought. When the Crusaders sacked and desecrated Constantinople in 1204 (an act unthinkable in earlier centuries for the Christian West), they only revealed that they had become total strangers to Orthodoxy, and therefore to the Eastern Christians, and that they had irretrievably lost what their own ancestors in 6th century Gaul had preserved as the apple of their eye: the unbroken tradition of true Christianity.

We shall mention here only some of the most obvious Orthodox forms of 6th century Gaul, as a helpful background to the reading of St. Gregory’s Life of the Fathers.

The Christian Temple: The Basilica

When Christians finally emerged from the catacombs in the reign of St. Constantine the Great, it was natural that they should begin to build churches in great numbers. For nearly three centuries, under conditions of persecution and the threat of persecution, the basic forms of Christian faith and piety had been nurtured literally underground and in private home churches; now, with Orthodox Christianity first given freedom, and then recognized as the religion of the State, Christian houses of worship were erected in conspicuous places in all cities and major towns of the Roman Empire, in East and West alike. The type of building found most suitable to the needs of Christian worship was not the pagan temple, where idols were worshipped in dark and confining interiors, but the Roman basilica or “royal hall,” a secular building used and adapted for various public functions, in many of which the emperor himself would be present (whence the name). Such buildings are known from the second century B.C., but the first Christian basilica dates only from shortly before the time of St. Constantine, and the 4th century is the first great age of its construction. For many centuries this was the standard Christian temple both in East and West; in style there is bin little variation from Syria to Spain and Britain, from Africa to Germany. It is from the basilica that the Christian temples of later centuries, whether East or West, are derived.

The standard basilica plan includes a long nave (where the believers would stand), usually flanked by aisles on both sides, ending in a semi-circular apse where (he sanctuary or altar-area was located; often there was a narthex in the rear and an atrium or courtyard outside with a fountain where the faithful would wash their hands before entering the church The nave was supported by columns which separated it from the aisles, and the columns were topped by a band of wide windows which gave abundant opaque light (being made of mica or similar material, there being no glass then) which rendered especially bright the iconographic mosaics or (more commonly in Gaul) frescoes which adorned the apse and the upper walls of the basilica. The interior was also ornamented with numerous gold decorations, chandeliers, etc. The basic structure would be of stone or brick, surmounted by a flat ceiling, with open timbers usually visible. Already by the 6th century, the flat roof was often replaced by a dome.

There are a number of excellently preserved basilicas especially from the 5th and 6th centuries in Rome and Ravenna, and many others are well known from foundation remains, excavations, and contemporary descriptions. The first impression created by such buildings is one of majesty and beauty. This is the aspect emphasized in the first detailed descriptions we have of a Christian basilica, that of the Basilica of Tyre in the East (consecrated in 317), in the Church History of Eusebius (Book X, 4): “The basilica itself he (the builder) has furnished with beautiful and splendid materials, using unstinted liberality in his disbursements. Its splendor and its majesty surpass description, and the brilliant appearance of the work, its lofty pinnacles reaching to the heavens, and the costly cedars of Lebanon above them … the skillful architectural arrangement and the surpassing beauty of each part.”

The purpose of such splendor is to inspire and elevate one, to open up a new heavenly world to those born of earth. But the entrance to this world is gained only by those who go on the narrow path of ascetic Christianity. To remind the faithful of this, St. Paulinus had his own verses inscribed over the doors to his basilica in Nola in Italy (early 5th century). Over one door he wrote: “Peace be upon you who enter the sanctuary of Christ with pure minds and peaceful hearts”; over another, together with a representation of the cross: “Behold the wreathed cross of Christ the Lord, set above the entrance hall. It promises high rewards for grinding toil. If you wish to obtain the crown, take up the cross”; and inside one door, visible to the people as they leave: “Each of you that departs from the house of the Lord, after completing your prayers in due order, remove your bodies but remain here in heart.” (St Paulinus of Nola, Letter 32.)

Unfortunately, none of the basilicas of Gaul in this period has survived, but from the numerous literary descriptions of them that we do have it is obvious that they were identical in style to those of Rome and the East. From descriptions in the writings of St. Gregory of Tours it has been possible to reconstruct the approximate appearance of the Basilica of St. Martin in his time. He has an interesting description also of the basilica of his native Clermont, built by St. Namatius in the 5th century: “It is 150 feet long, 60 feet wide inside the nave, and 50 feet high as far as the vaulting. It has a rounded apse at the end, and two wings of elegant design (one variation of the basilica-style) on either side. The whole building is constructed in the shape of a cross. It has 42 windows, 70 columns, and eight doorways. In it one is conscious of the fear of God and of a great brightness, and those at prayer are often aware of a most sweet and aromatic odor which is being wafted towards them. Round the sanctuary it has walls which are decorated with mosaic work made of many varieties of marble.” (History of the Franks, II, 16.)

Between the nave and the altar area there was often, even in the earliest Christian basilicas, a kind of screen. A description and explanation of this is given by Eusebius when, in describing the Basilica of Tyre, he ends with “the holy of holies, the altar, and, that it might be inaccessible to the multitude, he enclosed it with wooden lattice-work, accurately wrought with artistic carving, presenting a wonderful sight to the beholders.” Evidently, from the very moment the Church left the catacombs, it was felt necessary to screen the holy of holies from the people so that the Mysteries might not be profaned by the ever-present temptation, in times of peace and ease, to take them for granted. This screen, the “chancel,” is the beginning of the later iconostasis in the East and the roodscreen in the medieval West. Many traces of the chancel may be seen in the oldest Roman basilicas today, and in all likelihood they were present in the basilicas of Gaul as well.

The altar-tables in the early Christian basilicas were virtually identical with those still used in the Orthodox East, rather than with the later elaborate Latin altars of the West. Made at first usually of wood, and later of stone, they were generally square in shape, as is the oldest surviving altar-table of Gaul, found at Auriol near Marseilles (5th century). The altar-tables visible in the 6th century mosaics of Ravenna square and entirely hidden by cloth coverings, are in no way different from the altar-tables that may be seen in any Orthodox church today.

The saint to whom a basilica would be dedicated would be most often buried under the altar, sometimes in a special crypt; thus it was in the Basilica of St. Martin in Tours.

Baptisms were conducted in a separate building (baptistery) near the basilica. Several baptisteries from this period have been well preserved in Italy, and the baptistery in Poitiers is the only substantially intact church building of the whole Merovingian (pre-Charlemagne) period in Gaul.

The church furnishings of the basilica would be familiar to today’s Orthodox Christian. There would be many oil-burning lamps, some in chandeliers hanging from the roof, others before the tombs of saints or before icons or relics. The poet Fortunatus and his fellow student Felix were healed of an eye affliction by rubbing the affected spot with oil from the lamp burning before the icon of St. Martin in his church in Ravenna. A remarkable miracle in the Life of St. Gregory of Tours (ch. 22) occurred with the oil lamp which hung before the relic of the Holy Cross in St. Radegund’s convent in Poitiers. Beeswax candles were used, both as offerings and carried in processions.

The vestments of the clergy were also very similar to those still in use today in the Orthodox Church. The characteristic vestment of deacons (who at this time were still a separate order of the clergy, as in the East today, and not simply a stage on the way to the priesthood, as they became in the Latin church), was the alb, a long white tunic of silk or wool, identical with the Eastern sticharion; later in the West this was much modified. Deacons also wore a stole or orarium over the left shoulder—the orarion of Orthodox deacons today. Priests wore the chasuble, which in distinction from the Eastern phelonion had a hood (cucullus), as mentioned in the Life of the Fathers (VIII, 5), and also wore cuffs, as in the East today. The distinctive mark of the bishop was the pallium (given only to some bishops in the beginning), which in later centuries became much simplified in the Latin church, but in this period, according to Prof. Dalton, “in form corresponded almost exactly with the omophorion of the Greek Church” (vol. 1, p. 334). These vestments were chiefly adapted for use from the ceremonial dress of the Roman imperial court; as in the case of the Christian basilica, the Church used for its external forms what it found when it emerged from the catacombs and hallowed it for use by succeeding generations.

The daily cycle of services followed the same pattern which has been preserved up to now in the Orthodox Church: Vespers and Matins, the Hours (First, Third, Sixth and Ninth), Compline and Nocturn. The specific content of the services (for example, which psalms were read in which services) was different from that of the East, but the general nature of the material used (psalms, antiphons taken from the psalms, readings from the Old and New Testaments, newly-composed hymns) was the same. Nocturn and Matins were combined to form the Vigil (vigilia) before the great feasts. The services in monasteries were generally longer than those in parish churches and cathedrals.

The Gallican Rite, which differed from the Roman Rite in a number of details, was used in Gaul and Spain. Attempts have been made in modern times to reconstruct this rite, which was supplanted in Gaul by the Roman Rite in the 8th and 9th centuries, and later died out completely in the West; but the texts from this period that have come down to us give only the general outline of some of the services, and not their full texts. The Gallican Mass (missa, as the Liturgy was universally called in the West) has some interesting points of agreement with the Eastern Liturgy as opposed to the Roman Mass, most notably the presence of a “Great Entrance” with the unconsecrated bread and wine after the dismissal of the catechumens. However, even the Latin Mass at this time was less different from the Eastern Liturgy than it became in later centuries, and no problems were encountered on the frequent occasions when Christian clergy from the West would concelebrate the Liturgy in Constantinople, or Eastern clergy would do so in Rome.

The liturgical year was basically the same as that known today in East and West alike. Great feasts such as Christmas and Epiphany, Pascha, the Ascension and Pentecost were celebrated with special solemnity, as were saints’ days such as those of St. John the Baptist and Sts. Peter and Paul. The Calendar of saints in the Roman Church included many thousands of names, and the memory of local saints was kept with great reverence; in Tours, as St. Gregory informs us, special vigils were kept for the feasts of Sts. Martin, Litorius and Bricius or Tours, St. Symphorian of Autun, and St. Hilary of Poitiers (HF X, 31). Whereever there were relics of saints, they were venerated with special solemnity; the relics of St. Martin in Tours, in particular, were the object of pilgrimages from all over Gaul. The fast of Great Lent was kept strictly, and Wednesdays and Fridays of most weeks were fast days, in addition to extra fast days before Christmas and at other times.

The days of rogation mentioned by St. Gregory were special days of fasting and prayer before the feast of the Ascension; these were instituted by St. Mamertus of Vienne in the 5th century and later spread to the whole of Gaul and the West (HF II, 34).

6th Century Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna

Interior of the Basilica of St. Demetrius in Thessalonica (5th century)

Apse of the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna

Mosaic from the Church of San Vitale, Ravenna (showing Altar-table in use in the 6th century)

Right wall of the nave, showing procession of the martyrs, in Saint Martin’s Basilica in Ravenna (Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo)

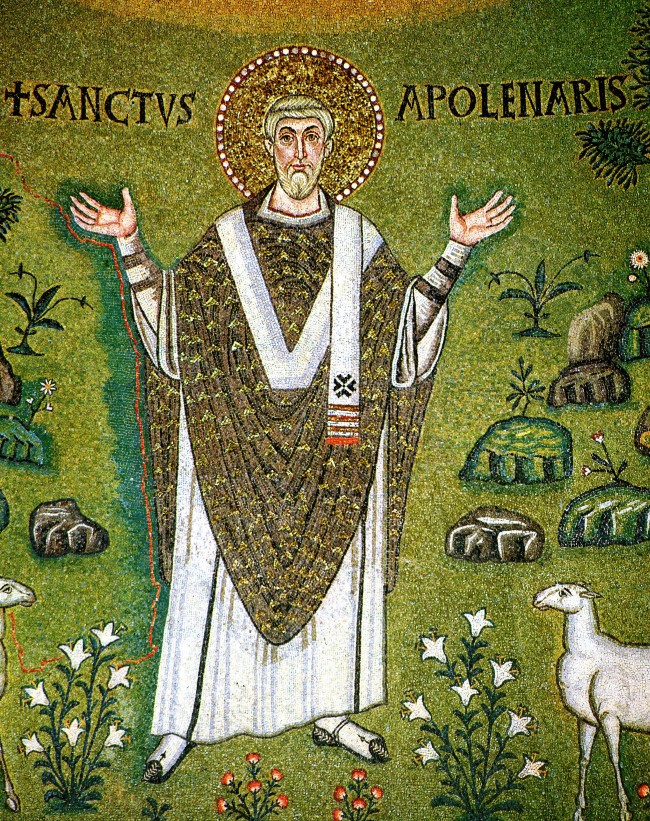

St. Apollinaris, first Bishop of Ravenna with the priestly vestments in use in the 6th century: alb (sticharion), chasuble (phelonion), cuffs, and the bishop’s pallium (omophorion) (Mosaic from the apse, Sant’ Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna)

The Baptistery in Poitiers (the only surviving church building of Merovingian Gaul)

The earliest altar-table of Gaul still extant (found ant Auiol near Marseilles)

Iconography

From the beginning, the Christian basilicas were adorned with mosaics or frescoes, at first in the apse, and very soon on the walls as well. Those in Gaul were lost together with the churches that housed them, and so we can only judge of them by contemporary descriptions and by surviving examples, especially in Italy, which was in close contact with Gaul at this time.

The iconography of the 4th century is rather close in style to the realism of later Roman painting, although by the end of the century, even in Rome, it is already changing towards the Byzantine style; in content it combines themes from the symbolic paintings of the catacombs (Christ as the Lamb, the Good Shepherd, etc.) with scenes from the Old and (more and more with time) from the New Testament. The Basilica of St. Ambrose in Milan, dedicated in 386, contained frescoes (as we know from the inscriptions of the Saint himself) from the Old Testament, and the following ones from the New Testament: the Annunciation, the conversion of Zacchaeus, the woman with an issue of blood, the Transfiguration, and St. John leaning on the breast of the Saviour. Judging from the contemporary mosaics at St. Pudentiana in Rome, the style of these icons was already very close to the later Byzantine style. In the Basilica of St. Paulinus in Nola (404), the two sides of the nave contained scenes from the Old and New Testaments, and in the space between the windows above were apostles and saints, with Christ the King in the apse. There was as yet no fixed rule for the depiction of various feasts or scriptural events, and there was no formal canonization of the saints who might be portrayed in icons; apostles, martyrs, and even recent Bishops and ascetics were depicted according to their local veneration. There is even a case where, in the baptistery of the monastery of Sulpicius Severus at Primuliacum in southern Gaul, the recently-reposed St. Martin is depicted on one wall, and the still-living Bishop Paulinus of Nola on the opposite wall—something which aroused the good-natured protest of St. Paulinus, who wrote Severus: “By depicting me alone on the opposite wall, you have contrasted my lowly figure, shrouded in mental darkness, with Martin’s holy person” (St. Paulinus, Letter 32).

The distinctive Byzantine style is already evident in the 5th century, and the 6th century is the age of an already developed and perfected art. The great basilicas of Ravenna are monumental triumphs of Byzantine iconography—an art which in style and subject-matter has not changed essentially through the ages, and is still very much alive today. The Byzantine style was universal in the Roman Empire, as may be seen in the icons even of the remote border area of Mt. Sinai, where the mosaic of the Transfiguration in the apse is identical with later icons of the feast down to our day. This is the Christian art that was known to the great Western hierarchs of the 6th century, St. Gregory, Pope of Rome, and St. Gregory of Tours.

In Gaul, mosaic icons are known (HF II, 16; X, 45), but more commonly we hear of frescoes. The original basilica of St. Martin had frescoes which were restored by St. Gregory, as he himself relates (HF X, 31): “I found the walls of St. Martin’s basilica damaged by fire. I ordered my workmen to use all their skill to paint and decorate them, until they were as bright as they had previously been.” These frescoes must have been impressive, for when treating of the stay of a certain Eberulf in the basilica (under the law of sanctuary which then prevailed), St. Gregory writes: “When the priest had gone off, Eberulf’s young women and his men-servants used to come in and stand gaping at the frescoes on the walls” (HF VII, 22). St. Gregory has preserved for us also a brief account of how the frescoes were painted (5th century): “The wife of Namatius built the church of St. Stephen in the suburb outside the walls of Clermont-Ferrand. She wanted it to be decorated with colored frescoes. She used to hold in her lap a book from which she would read stories of events which happened long ago, and tell the workmen what she wanted painted on the walls” (HF II, 17). This “book” might have been the Scriptures, the Life of a saint, or even, as Prof. Dalton suggests, “some sort of painter’s manual like those used in the East” (vol. 1, p. 327).

When restoring the main basilica of Tours (distinct from the basilica where St. Martin’s relics reposed), as Abbot Odo informs us precisely in his life of St. Gregory (ch. 12), the latter “decorated the walls with histories having for subject the exploits of Martin.” It so happens that we have a list of these iconographic scenes in a poem of Fortunatus describing the basilica (Carmine X, 6). They are: (1) St. Martin curing a leper by a kiss; (2) dividing his cloak and giving half to a beggar; (3) giving away his tunic; (4) raising three men from the dead; (5) preventing the pine tree from falling on him by the sign of the Cross; (6) idols being crushed by a great column launched from heaven; (7) St Martin exposing a pretended martyr. We can only regret the disappearance of such a notable monument of Orthodox Christian art, just one of many in 6th century Gaul, the likes of which were not to be seen in later but we may gain a general idea of its appearance in the contemporary basilicas of Ravenna with their mosaic icons. One of these basilicas, indeed, was dedicated originally to St. Martin of Tours, the dedication later being changed to Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

Separate panel icons also existed at this time. In the history of Bede it is stated that St. Augustine of Canterbury and those with him, after landing in Britain in the year 597, came to King Ethelbert of Kent “bearing a silver cross for their banner, and the image of our Lord and Saviour painted on a board” (Ecclesiastical History of England, Book I, ch. 25). In the Life of the Fathers (XII, 2) we read of “the icons (Latin iconicas) of the apostles and other saints” in the oratory where St. Bracchio prayed. It should be noted that the oratories and small village churches of Gaul would not, of course, be in basilica style or usually made of stone; they were generally of wood, and the icons in them were painted on boards and hung on the walls. The most detailed reference to these 6th century panel icons is in St. Gregory’s Glory of the Martyrs (ch.22), where we read, in the account “of the Jew who stole an icon (Latin iconica, or in one manuscript, icona) and pierced it,” the following, which is also an

impressive testimony of the truly Orthodox attitude of the Church of Gaul at this time, as contrasted with the iconoclast sentiment which seized part of Gaul (as it did also of the Christian East) in the century of Charlemagne. Here are St. Gregory’s words:

“The faith which has remained pure among us up to this day causes us to love Christ with such a love that the faithful who keep His law engraved in their hearts wish to have also His painted image, in memory of His virtue, on visible boards which they hang in their churches and in their homes… A Jew, who often saw in a church an image of this sort painted on a board (Latin imaginem in tabula pictam) attached to the wall, said to himself, ’Behold the seducer who has humiliated us’… Having come then in the night, he pierced the image, took it down from the wall, and carried it under his clothes to his house in order to throw it into the fire.”

He was discovered when it was found that the image shed copious blood in the place where it had been pierced (a miracle which occurred also later in Byzantium with the Icon of the Iviron Mother of God, and in Soviet times in Kaplunovka in Russia with a crucifix).

A number of such panel icons on wood have come down to us from 6th century Mount Sinai; they are identical in appearance to the icons which pious Orthodox Christians cause to have painted for their churches and homes even today.

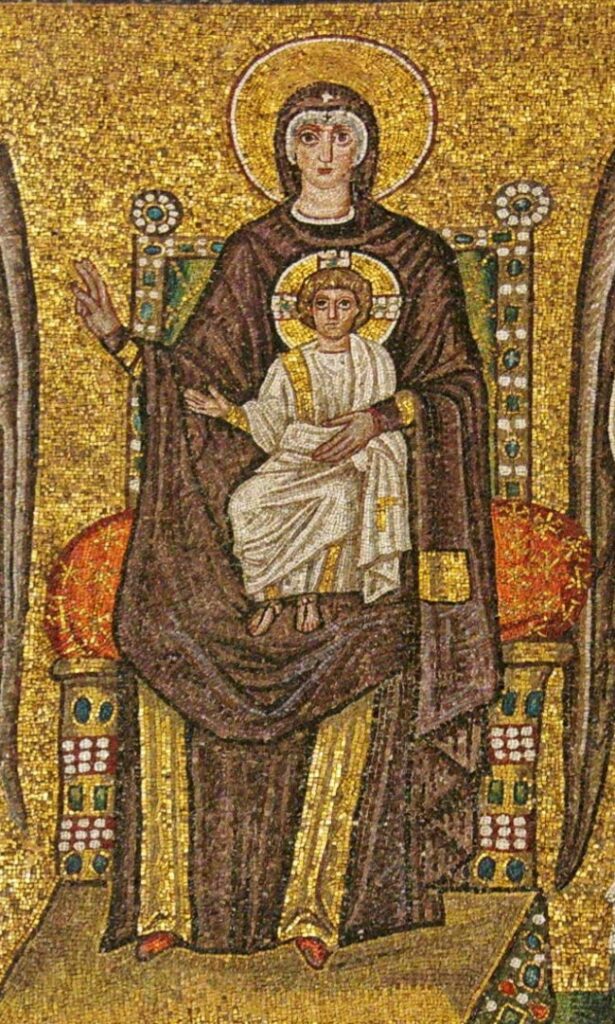

The Most Holy Theotokos – 6th century Mosaic in St. Martin’s basilica (Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna)

Saint Martin of Tours – Probably the earliest surviving icon of the Saint (Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna)

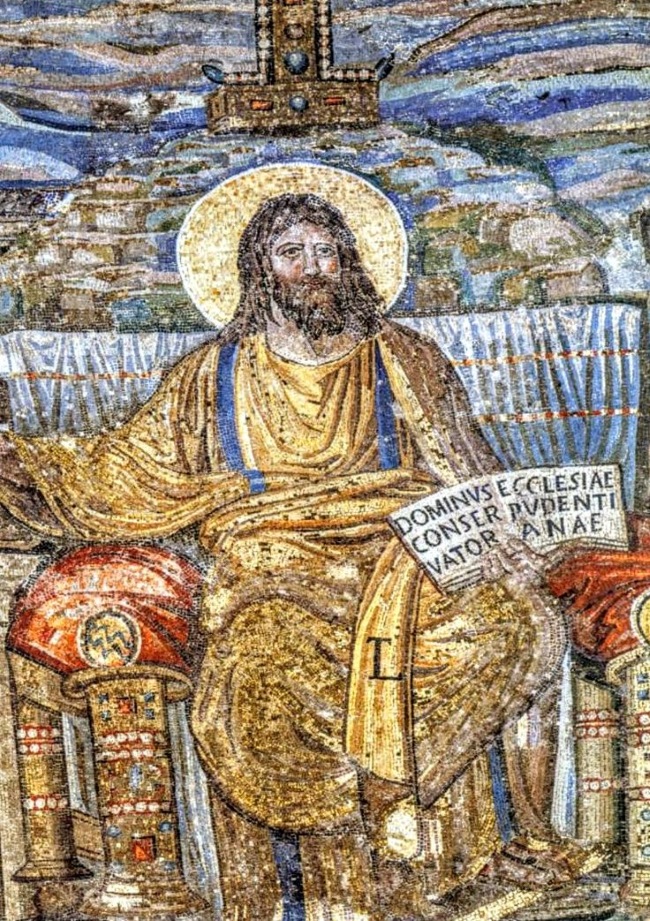

Mosaic of Christ from the Basilica of St. Pudentiana, Rome, about 385

6th Century Mosaic of Christ, from Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

The Transfiguration of Christ (6th century mosaic at M. Sinai)

Saint Martin before the Saviour (Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna)

Church Organization

The Church government of Gaul in the 6th century was, in the words of Prof. Dalton, according to the “Eastern system” (vol. 1, p. 268)—that is, according to Orthodox and not Papal principles.

At this time there were about 130 bishops in Gaul, of whom eleven were Metropolitans, or bishops of the chief cities of the land, with certain rights of precedence over the other bishops of the metropolitan district. The Metropolitans of Arles (in the south) usually held a seniority over the other Metropolitans, and especially during the episcopate of St. Caesarius of Arles (first half of the 6th century), it was he who convoked and presided over councils of bishops. There were no vicar bishops; each bishop governed his own see, and questions affecting many bishops were decided in councils, where all the bishops had an equal voice.

The Pope of Rome, while of course respected as Patriarch of the West, was still “first among equals” and exercised authority about equal to that exercised in later centuries (before the fall of Byzantium) by the Patriarch of Constantinople over the Church of Russia. Pope Gregory the Great at this time specifically protested against the assumption by the Patriarch of Constantinople (or any Patriarch, including himself) of the title “Ecumenical Patriarch”: “What will you say to Christ, Who is the Head of the universal Church, in the scrutiny of the last judgment, having attempted to put all His members under yourself by the appellation of Universal… Certainly Peter, the first of the Apostles, himself a member of the universal Church, Paul, Andrew, John,—what were they but heads of particular communities… And of all the saints, not one has asked himself to be called universal… The prelates of this Apostolic See, which by the Providence of God I serve, had the honor offered them of being called universal… But yet not one of them has ever wished to be called by such a title, or seized upon this ill-advised name, lest if, in virtue of the rank of the pontificate he should take to himself the glory of singularity, he might seem to have denied it to all his brethren.” (Letters of St. Gregory the Great, Book V, 18).

The very title of “apostolic see,” although applied with special reverence to the See of St. Peter, was in this period given not only to Rome but to all episcopal sees, at least in Gaul, as may be seen in the letter of St. Radegund preserved in the History of the Franks (IX, 42): “To the holy fathers in Christ and to the lord Bishops, worthy occupants of their apostolic sees…” The “apostolic see” of Bordeaux is mentioned specifically by St. Gregory in the History of the Franks.

Even the famous case of St. Hilary of Arles, which is sometimes viewed as an example of “Papal intervention” in the affairs of the Church of Gaul, in the eyes of Pope St. Leo himself had entirely another meaning. The Pope—who, indeed, was recognized as having jurisdiction when appealed to by other bishops in the West—overturned St. Hilary’s deposition in 444 of a certain bishop in Gaul, whom St. Leo found innocent of the charge against him, not in the name of any “Papal rights” but rather with the intention of restoring the ancient rights of the local bishops of Gaul. He accused St. Hilary of “claiming for himself the ordinations of all the churches throughout the provinces of Gaul, and transferring to himself the dignity which is due to Metropolitans,” thus “claiming for himself the ordinations of a province for which he was not responsible.” St. Leo concludes his letter to the bishops of the Gallic province of Vienne: “We are not keeping in our own hands the ordinations of your provinces, but we are claiming for you that no further innovations should be allowed, and that for the future no opportunity should be given for the usurper to infringe your privileges.” (Letters of St. Leo the Great, Letter X.)

It was only in later centuries that Papal “universality” began to be asserted by the Popes, and only after the Schism that the present-day concept of “Papalism” was developed. In the 5th and 6th centuries the government of the Church of Gaul was very much in the “Eastern” way. The Metropolitans had no direct jurisdiction even over the bishops of their own province. When Felix, Bishop of Nantes, made false accusations against St. Gregory of Tours, his own Metropolitan, out of spite for being unable to take away some church property from the latter’s diocese, St. Gregory could do nothing but express his exasperation at such un-Christian conduct in a reply not lacking in St. Gregory’s dry humor: “What a pity that it was not Marseilles that elected you its bishop! Instead of bringing you cargoes of oil and other wares, its ships could have carried only papyrus, which would have given you more opportunity for writing libelous letters to honest folk like me” (HF V, 5).

Conclusion: the meaning of sixth-century Gaul for today

To sum up this brief description of 6th century Christian Gaul, we may say that here we find already the historical Orthodox world which is familiar even today to any Orthodox Christian who is at home in true (not modernized or renovated) Orthodoxy. The scholar of Late Latin could find ample opportunities for further research in this field, whether in the works of St. Gregory of Tours or in numerous other texts of this time (which have been surprisingly little studied or translated up to now); the material given above is no more than an introduction. In modern times, 6th century Gaul may most accurately be likened to 19th century Russia. Both societies were entirely permeated with Orthodox Christianity; in them the Orthodox standard was always the governing principle of life (however short of it the practice might fall), and the central fact in the life of the people was reverence for Christ, the holy things of the Church, and sanctity. In the 6th century (as opposed to the 4th, which is still a time of development), the outward things of the Church had already received their more-or-less final forms, which subsequently changed very little in the Orthodox East; thus, we are able to feel very much at home with them. At the same time, there is a freshness and newness about the Church’s forms and its life which is very inspiring to us today, when it is very easy either to take the age-old forms of Orthodoxy for granted, or to feel that they have no “relevance” to modern life.

So much for the outward side of Orthodoxy; but what of its inward side? Does the Christian world of St. Gregory of Tours have any spiritual significance for us today, or is it of no more than antiquarian interest for us, the “out-of-date” Orthodox Christians of the 20th century?

Much has been written in modern times of the “fossilized” Orthodox Church and its followers who, when they are true to themselves and their priceless heritage, simply do not “fit in” with anyone else in the contemporary world, whether heterodox Christians, pagans, or unbelievers. If only we could undersand it, there is a message in this for us, concerning our position among others in the world and our preservation of the Orthodox Faith.

Perhaps no one has better expressed the modern world’s bewilderment over genuine Orthodox Christianity than a renowned scholar precisely of St. Gregory of Tours and the Gaul of his times. In his book, Roman Society in Gaul in the Merovingian Age (London, 1926), Sir Samuel Dill has written:

“The dim religious life of the early Middle Ages is severed from the modern mind by so wide a gulf, by such a revolution of beliefs that the most cultivated sympathy can only hope to revive it in faint imagination. Its hard, firm, realistic faith in the wonders and terrors of an unseen world seems to evade the utmost effort to make it real to us” (p. 324). “Gregory’s legends reveal a world of imagination and fervent belief which no modern man can ever fully enter into, even with the most insinuating power of imaginative sympathy. It is intensely interesting, even fascinating. But the interest is that of the remote observer, studying with cold scrutiny a puzzling phase in the development of the human spirit. Between us and the early Middle Ages there is a gulf which the most supple and agile imagination can hardly hope to pass. He who has pondered most deeply over the popular faith of that time will feel most deeply how impossible it is to pierce its secret” (p. 397).

And yet, for us who strive to be conscious Orthodox Christians in the 20th century it is precisely the spiritual world of St. Gregory of Tours that is of profound relevance and significance. The material side is familiar to us, but that is only an expression of something much deeper. It is surely providential for us that the material side of the Orthodox culture of Gaul has been almost entirely destroyed, and we cannot view it directly even in a museum of dead antiquities; for that leaves the spiritual message of his epoch even freer to speak to us. The Orthodox Christian of today is overwhelmed to open St. Gregory’s “Books of Miracles” and find there just what his soul is craving in this soulless, mechanistic modern world; he finds that very Christian path of salvation which he knows in the Orthodox services, the Lives of the Saints, the Patristic writings, but which is so absent today, even among the best of modern “Christians,” that one begins to wonder whether one is not really insane, or some literal fossil of history, for continuing to believe and feel as the Church has always believed and felt. It is one thing to recognize the intellectual truth of Orthodox Christianity; but how is one to live it when it is so out of harmony with the times? And then one reads St. Gregory and finds that all of this Orthodox truth is also profoundly normal, that whole societies were once based on it, that it is unbelief and “renovated” Christianity which are profoundly abnormal and not Orthodox Christianity, that this is the heritage and birthright of the West itself which it deserted so long ago when it separated from the one and only Church of Christ, thereby losing the key to the “secret” which so baffles the modem scholar—the “secret” of true Christianity, which must be approached with a fervent, believing heart, and not with the cold aloofness of modern unbelief which is not natural to man but is an anomaly of history.

But let us just briefly state why the Orthodox Christian feels so much at home in the spiritual world of St. Gregory of Tours.

St. Gregory is an historian; but this does not mean a mere chronicler of bare facts, or the mythical “objective observer” of so much modern scholarship who looks at things with the “cold scrutiny” of the “remote observer.” He had a point of view; he was always seeking a pattern in history; he had constantly before him what the modern scientist would call a “model” into which he fitted the historical facts which he collected. In actual fact, all scientists and scholars act in this way, and any one who denies it only deceives himself and admits in effect that his “model” of reality, his basis for interpreting facts, is unconscious, and therefore is much more capable of distorting reality than is the “model” of a scholar who knows what his own basic beliefs and presuppositions are. The “objective observer,” most often in our times, is someone whose basic view of reality is modern unbelief and scepticism, who is willing to ascribe the lowest possible motives to historical personages, who is inclined to dismiss all “supernatural” events as belonging to the convenient categories of “superstition” or “self-deception” or as to be understood within the concepts of modern psychology-

The “model” by which St. Gregory interprets reality is Orthodox Christianity, and he not only subscribes to it with his mind, but is fervently committed to it with his whole heart. Thus, he begins his great historical work, The History of the Franks, with nothing less than his own confession of faith:

“Proposing as I do to describe the wars waged by kings against hostile peoples, by martyrs against the heathen and by the Churches against the heretics, I wish first of all to explain my own faith, so that whoever reads me may not doubt that I am a Catholic.” (“Catholic,” of course, in 6th century texts, means the same thing that we now mean by the word “Orthodox.”) There follows the Nicene Creed, paraphrased and with certain Orthodox interpretations added.

Thus in St. Gregory we may see the wholeness of view which has been lost by almost all of modern scholarship—another one of those basic differences between East and West that began only with the Schism of Rome. In this, St. Gregory is fully in the Orthodox spirit. In this approach there is a great advantage solely from the point of view of historical fact—for we have before us not only the “bare facts” he chronicles, but we understand as well the context in which he interprets them. But more important than this—particularly when it comes to chronicling supernatural events or the virtues of saints—we have the inestimable advantage of a trained observer on the spot, so to speak—someone who interprets spiritual events (almost all of which he knew either from personal experience or from the testimony of witnesses he regarded as reliable) on the basis of the Church’s tradition and his own rich Christian experience. We do not need to guess as to the meaning of some spiritually-significant event when we have such a reliable contemporary interpreter of it, and especially when his interpretations are so much in accord with what we find in the basic source books of the Orthodox East. We may place all the more trust in St. Gregory’s interpretations when we know that he himself was granted spiritual visions (as described in his life) and was frank in admitting when he did not see the spiritual visions of others (HF V, 50).

Sir Samuel Dill notes that access is denied him, as a modern man, to the world of St. Gregory’s “legends.” What are we, 20th century Orthodox Christians to think of these “legends”? Prof. Dalton notes, regarding the very book of St. Gregory which we are presenting here, that “his Lives of the Fathers have something of the childlike simplicity characterizing the Dialogues of St. Gregory the Great” (vol. 1, p. 21). We have already discussed, in the “Prologue” to this book, the value of this “childlikeness” for Orthodox Christians today, as well as the high standards of truthfulness of such Orthodox writers as St. Gregory the Great (as contrasted with the frequent fables of the medieval West). The extraordinary spiritual manifestations described by St. Gregory of Tours are familiar to any Orthodox Christian who is well grounded in the ABC’s of spiritual experience and in the basic Orthodox source-books; they sound like “legends” only to those whose grounding is in the materialism and unbelief of modern times. Somewhat ironically, these “legends” have now become a little more accessible to a new generation that has become interested in psychic and occult phenomena as well as actual sorcery and witchcraft; but for them also the whole tone of St. Gregory’s writings will remain foreign unless they obtain the key to its “secrets”: true Orthodox Christianity. St. Gregory s “wonders and terrors of an unseen world” open up for us another reality entirely from that of modern unbelief and occultism alike: the reality of spiritual life, which is indeed more unseen than seen, which does indeed account for many extraordinary phenomena usually misunderstood by modern scholarship, and which begins now and continues into eternity.

There is, finally, another aspect of St. Gregory’s writings which modern historians find generally not so much baffling as disdainfully amusing, but to which, again, we Orthodox Christians have the key which they lack. This aspect is that of the “coincidences,” omens, and the like, which St. Gregory finds significant but which modern historians find totally irrelevant to the chronicling of historical events. Some of these phenomena are manifestations of spiritual vision, such as the naked sword which St. Salvius (and no one else) saw hanging over the house of King Chilperic, portending the death of the king’s sons (HF V, 50). But other of the manifestations are simply dreams or natural phenomena of an extraordinary kind, which either fill St. Gregory with foreboding (HF VIII, 17) or of which he says in all simplicity, “I have no idea what all this meant” (HF V, 23). The modern historian is only amused at the idea of finding a “meaning” behind earthquakes or strange signs in the sky; but St. Gregory, as a Christian historian, is aware that God’s Providence is at work everywhere in the universe and can be understood even in small or seemingly random details by those who are spiritually sensitive; he sees also that the deepest causes of historical events are by no means always the obvious ones. Concerning this theological point we may cite the words of a contemporary of St. Gregory in the East, St. Abba Dorotheus, to whom the writings of St. Gregory would have been not in the least strange.

“It is good, brethren, to place your hope for every deed upon God and to say: Nothing happens without the will of God; but of course God knew that this was good and useful and profitable, and therefore he did this, even though this matter also had some outward cause. For example, I could say that inasmuch as I ate food with the pilgrims and forced myself a little in order to be host to them, therefore my stomach was weighed down and there was a numbness caused in my feet and from this I became ill. I could also cite various other causes (for one who seeks them, there is no lack of them); but the most sure and profitable thing is to say: In truth God knew that this would be more profitable for my soul, and therefore it happened in this way.” (St. Abba Dorotheus, Spiritual Instructions, Instruction 12.)

St. Gregory, like St. Abba Dorotheus, was always seeking first of all the primary or inward causes of events, which concern the will of God and man’s salvation. That is why his history of the Franks, as well as of individual saints, are of much greater value than the “objective” (that is, purely outward) researches of modern scholars into the same subjects. This is not to say that some of his historical facts might not be subject to correction, but only that his spiritual interpretation of events is basically the correct, the Christian one.

It remains now, before proceeding to the texts of St. Gregory himself, to examine only one more major aspect of the historical context of The Life of the Fathers: the monasticism of 6th century Gaul. Here again we shall find St. Gregory’s Gaul very “Eastern,” and perhaps here more than in any other aspect of that early Orthodox age will we find cause for spiritual inspiration, and perhaps even some hints that will help our own poor and feeble Orthodox monasticism in the 20th century.

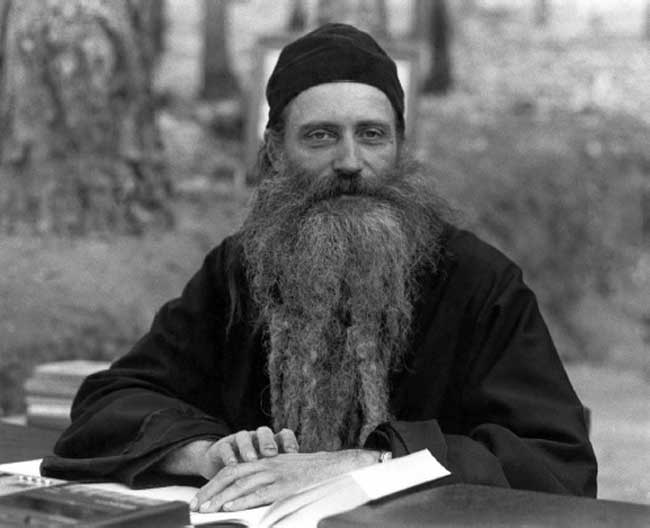

by Saint Seraphim of Platina [†1982]

The Orthodox Word, 1977, Vol. 13, No. 1 (72), January-February, pp. 14-38

Pas de commentaire