After the decision to restore the Patriarchate, the most important act of the Sobor was the election of the man to fill that office. In the midst of the three days battle which resulted in the taking of Moscow by the Bolsheviks, the Sobor in orderly sittings carried out the routine it had defined for the election of a Patriarch.

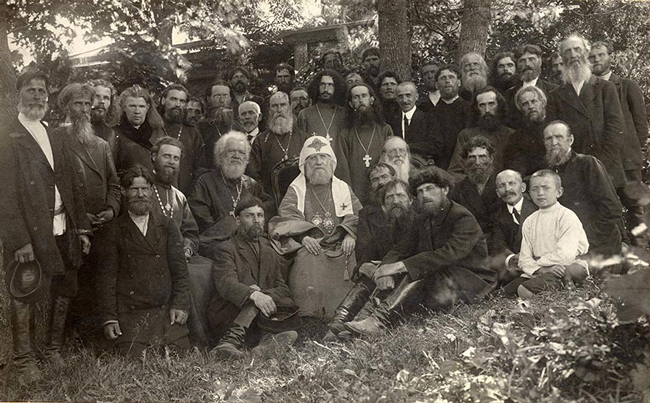

This was a minutely detailed procedure based upon the method first employed in 1634 for the election of Joasaf I and followed in the choice of all subsequent Patriarchs. A secret ballot of all members was taken and the names of those receiving votes tabulated according to the number received. The choice of the Patriarch must be made from the highest three in the list. In this case they were Tikhon, Metropolitan of Moscow, Antonius, Archbishop of Kharkov, and Arsenius, Archbishop of Novgorod. On November 5th, after a solemn service in the Church of the Savior, the three names, carefully sealed in wax rolls of equal size and weight, were placed in an urn and the eldest of the recluse-monks present drew out one name. It proved to be that of Tikhon, whose election was forthwith proclaimed. On November 21st (1917) occurred the solemn consecration in the Cathedral of the Assumption, and a new epoch in Russian church history had begun.

The man chosen to this high office was without question one of the most widely known and loved in all the Russian Church. He had been elected unanimously to the presidency of the Sobor. His appointment a few months earlier to the Metropolitanate of Moscow had simply indicated his prominence in Russian church affairs. The Patriarch is a native of Toropetz, a town near Pskov. His theological education was acquired in the Petrograd Academy, after which he served for three years as instructor in the Pskov Theological Seminary. In 1891 he took the monastic vow and after serving for six years as rector of the seminary in Kholm, he was consecrated Bishop of Lublin. One year later he was appointed Bishop of North America. In 1907 he returned to Russia as Bishop of Yaroslavl and in 1913 he became Bishop of Vilna, from which seat he was called four years later to the Metropolitanate of Moscow.

Patriarch Tikhon’s nine years in America were important ones in the affairs of the Orthodox Church there. During this period the episcopal seat was removed from San Francisco to New York. During this period Bishop Tikhon became Archbishiop Tikhon, the first American Orthodox hierarch to bear that title. These years made a deep impression upon the future Patriarch himself, and as will later be pointed out, the knowledge of the life and religious ideals of American people he acquired there have been very influential in later events in Russia. America has no better friend in Russia than Patriarch Tikhon and he seems especially pleased to maintain his connection with Americans and things American. In view of his unique position and significance for all the Orthodox Church, a brief sketch of the Patriarch as the author last saw him in November 1920, will possibly here be pertinent.

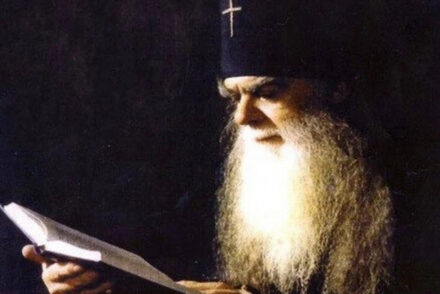

An erect, well-built man in a black robe: grey hair and beard which at first glance make him appear older than his fifty-six years: a firm handclasp and kindly eyes with a decided trace of humor and ever a hint of fire in the back of them: those are your first impressions. That, and his beaming smile. The next thing I thought of was how little he had changed in appearance in the two years since I last visited him. He does not look a day older, and his manner, in marked contrast to so many of my friends in Moscow, is just as calm, unhurried and fearless as though he had not passed through two years of terrible uncertainty and stress. He had put on the white silk cowl with its diamond cross and the six-winged angel embroidered above the brow which is the head-dress of the Patriarch on all official oceasions, but he had evidently just been sitting down to tea and the arrival of an old friend dispelled any formality. So in a minute the cape and gown had disappeared and we were sitting beside the samovar in his living room. First the Patriarch wanted to know all about the Church in America. The only recent news he had was a cablegram which had been over a year en route. Then I had to promise to convey his heartiest greetings and special blessing to a number of individuals and to “all American friends” in general.

He was most anxious to know if the letter he addressed to President Wilson on Thanksgiving Day, 1918, had ever reached him. In it the Patriarch had expressed his Church’s participation in offering thanks for victory over the powers of evil, and congratulated President Wilson on his fine type of leadership. The letter then went on to speak of the seemingly severe terms imposed upon the enemy, and urged Christian forbearance and the alleviation of the conditions laid down, rather than the creation of a lasting hatred which could but breed more war. No reply was ever received, and the Patriarch was curious to know if it had ever reached the President. Later, I tried to get a copy of this letter, but found that all extant copies had been destroyed during a political raid in the home of the Patriarch’s secretary.

All those who know Patriarch Tikhon enjoy his well-developed sense of humor. I believe it is this which has helped him retain his poise and cheerfulness through the past three years. I asked him how he had been treated. He told me he had been under “home arrest” for more than a year, had been permitted to go out to conduct service in other churches about once in three months, but aside from this had suffered no personal violence; this in marked contrast to many of the Church’s dignitaries who had been sent to jail or even condemned to execution. “They think”, the Patriarch smilingly remarked, as he patted my hand confidentially, “Oh, he’s an old chap: he’ll die soon … we won’t bother him”. “Wait and see”, he went on, shaking his finger, schoolmaster-fashion— »I’ll show them, yet”. And the roguish twinkle in his eyes, remarkably young in contrast to his grey hair, gave you confidence that when the present nightmare has cleared in Russia, her Church’s leader will be found ready to take a most active part in the affairs of the new day.

But not a political part: we spoke of several churchmen who had dabbled in politics, and the Patriarch expressed his sorrow and disapproval; ’What is right and just one may openly approve, and what is evil and unrighteous one must as openly condemn”, he said, “that is the Church’s business. But to meddle with the affairs of secular politics is neither the course of wisdom or of duty for a priest”.

“What is the most urgent need of the Orthodox Church which the Christian world outside can supply?” I asked the Patriarch.

“Send us Bibles”, he replied. “Never before in history has there been such a hunger for Scripture in the Russian people. They clamor for the whole book—not only the Gospels but the Old Testament as well—and we have no Bibles to give them. Our slender stocks were exhausted long ago, and our presses have been confiscated, so that we cannot print more”. I assured him that Christians in other lands would doubtless find a way to supply this need.

It happened to be Thanksgiving Day at home, and the Patriarch remembered, and smilingly referred to its being known as “Turkey Day” in an American family he used to visit in New York. This brought on a discussion of American and Russian holidays and this in turn led to an interesting conversation about the present religious situation in Russia. At every step in this recital the Patriarch’s clear insight into men and events and his statesmanlike grasp of the affairs of the whole Church were clearly evident. I left him with a renewed conviction of his fitness for the high post he occupies.

Russian Christians believe the choice of the Patriarch was directed by Divine Providence, and surely Patriarch Tikhon’s career thus far, offers basis for the belief. It would be difficult to imagine a man better fitted, mentally and temperamentally for the peculiarly difficult task of leading the Orthodox Church through these years of disorder and suffering in Russia. His good-humored friendliness, combined with a kindly firmness have become proverbial in the Russian Church. This is even more true of what Russians call his “accessibility”. It is common belief that anyone, be he bishop or priest or the most obscure layman, who has real need of his advice or decision, may get to see the Patriarch.

I recall a small incident which gives point to this statement. One day in 1918, late in the afternoon I called at the Patriarch’s house, by appointment, for in those troubled months the Patriarch was so busy and his presence so much in demand that we used to wonder when he found time for sleep. And as I passed through the hall I noticed a woman in a peasant’s dress, sobbing in a corner. In response to my question she poured out a long story of how some canonicaI difficulty in the marriage of her daughter could only be solved by the personal decision of the Patriarch. “I’ve been here since early morning”, she said, wiping her eyes, “without eating or drinking, and now they say the Patriarch is home from the Sobor but he is too busy to see me”. The tall servant in the hall, who by the way was also in America with Patriarch Tikhon, told me in English that he felt the Patriarch was too busy with matters of national importance to be troubled with one woman’s private request. Knowing the Patriarch as I did, I ventured to tell him of the petitioner in the hall, and as I left he asked to see her. In some Russian village today there is a peasant family who think Russia’s Patriarch is the kindest man who ever lived.

But these glimpses of fatherly kindness in the leader of the Russian Church must not be allowed to give a one-sided impression. On account of his good nature a Russian writer has compared him to the first Patriarch of Russia, Job. In view of his proven statesmanship and his fearless insistence upon justice as well as the remarkable skill with which he has held the Church together when everything else in Russia was falling into ruin, it seems to me he more nearly resembles Hermogen, whose influence moved so powerfully in unifying and inspiring Russian spirit to throw off the Polish yoke. From the closing of the Sobor in September, 1918, the Patriarch continued its policy of protest against increasing encroachments of civil powers upon church property and church direction. With constantly increasing severity the government punished anyone who questioned or opposed its decrees, so that to make a public protest was something which might bring the gravest personal consequences. The policy of Red Terror had gone into effect. In the face of this, the Patriarch issued his classic Epistle to the “Soviet of People’s Commissars”: — »Whoso taketh a sword shall perish by the sword”, it begins. “The blood of our brothers shed in rivers at your order, cries to Heaven and compels us to speak the bitter words of truth. You have given the people a stone instead of bread, a serpent instead of a fish. You have exchanged Christian love for hatred: in the place of peace you have kindled the flames of class enmity”. A few lines later we read “Is this freedom, when no one may openly speak his mind without danger of being accused as a counterrevolutionary? Where is the freedom of word and press? Where is freedom of church preaching?” The epistle concludes with the formal excommunication of all those connected with the terroristic movements in the government. He is a stern man and a bold one, who can publish such sentences in the face of powerful enemies against whom he has not the slightest physical defense. The Head of the Russian Church has been absolutely fearless in condemning wrong and insisting upon justice and right.

This boldness, tempered with a well-seasoned moderation, has enabled the Patriarch to maintain his position as leader and center of the whole church organization. With clear consistence he has refrained from interference with purely political affairs, save in so far as they touched upon matters of public morals or common justice. He is probably the only man of similar importance who was able to speak his mind so freely without punishment by imprisonment or worse, during four years of the Soviet government in Russia. His life during this time has been of the greatest importance to the Russian Church. In his person all Orthodox thinking has centered. His personality has kept alive the spirit of a Church unified in a time when every other institution had gone to pieces. His example has inspired new ideals of religion and life in the hearts of millions of his people.

Chaotic as these years have been, they have witnessed at the same time a momentous deepening of religious feeling and spirit in Russia. Religion has become in the lives of most people something far more than ever before. What once was more or less formal theory has now been transmuted by the fires of the past four years into vivid reality, into lifeblood to strengthen men and women through boundless hardship. In the old days, one was often charmed by the peculiarly intimate and conscious sense of God shown by a peasant or a workman, something one finds much more rarely in western lands. Now, it is an experience to make one stop and think, to discover in the lives of the “intelligentsia”, as well, exactly the same vivid certainty of God’s presence and of the actuality of communion with Him. Is it something they have just learned, in these years of trial, or have they simply rediscovered the sense of God which has been latent all their lives? I think most Russians feel the latter is true, although most of the people I know frankly confess that never before has religion meant so much to them.

The Countess L. is an example of what I mean. As one knew her in the old days she was typical of her class of the “intelligentsia” in her attitude toward the church and toward religion in general: a mild respect for the feeling of other people in matters religious but a very frank skepticism, at least on the surface, so far as her own interest in religion was concerned. That was three years ago. The reign of terror and the general suffering of these years have not passed her by, and she has undergone such experiences as at once horrify you and inspire you by the heroism exhibited. Today she is a striking personality, who impresses you primarily in a religious way. It is difficult to say what it is about Countess L. which so inspires you, whether it is her serene faith in the goodness of God and the power of prayer, her sincere charity toward those who have caused her so much ill, or the transparently beautiful character which has grown in the midst of so much sorrow. I only know that a talk with her makes one’s own faith seem so small and one’s own religion so puny, that you are driven to a resolve to deepen your own spiritual life, and make it count more than ever before for the service of others.

By Donald A. Lowrie

Donald A. Lowrie, The Light of Russia—An Introduction to the Russian Church, The YMCA Press Ltd., Prague, 1923, pp. 217–225.

Pas de commentaire