The decision to call an All-Russian Sobor had been taken by Emperor Nicholas II after the Revolution of 1905–6. Serious preparatory work was accomplished. The question of the restoration of the Patriarchate seemed to become the central subject of the Sobor. After the Revolution of 1917, the restoration of the Patriarchate became imminent. A special committee was formed to prepare the election of the Sobor and to make all the necessary arrangements.

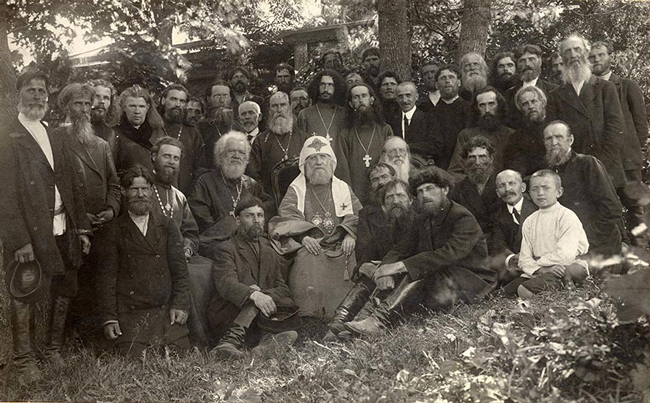

The new metropolitan of Moscow was a member of this committee and was specifically charged with arranging the reception and housing of all the members who would attend the Sobor. Over than sixty bishops were expected, and Tikhon personally visited all the nearby monasteries and checked the accommodations. He also decided where the various meetings were to be held and which churches would be used. It was not until late July that the elections began, for the actual request for voting was not issued until July 15th. Two ecclesiastical delegates and three laymen were selected from each diocese by indirect elections. Delegates also were sent from some monasteries, the four academies, military corps, and universities. Also, all bishops who were members of the pre-sobor council were considered ex-officio members.[1]

On August 11, the Provisional Government gave the coming Sobor the right to work out a new form of church government that was to be submitted to the Ministry of Confessions for approval. On August 16, the Sobor was opened with a solemn service, and various messages, chiefly relating to the chaos of the time, were read by Metropolitan Tikhon; S. K. Rodionov representing the Moscow Zemstvo; M. V. Rodzianko, former president of the Duma, and Arch-priest Lakhostsky. By a vote of 407 to 33, Metropolitan Tikhon was elected president of the Sobor, and throughout the meetings, he faithfully presided, often under most trying circumstances.

The main problem before the Sobor was the question of reviving the patriarchate[2]. The consensus of opinion was for such a revival for many reasons. Some saw it as the only salvation for the future of Russia, and these individuals cited past incidents[3] in Russian history as examples. Others believed that only with a strong religious leader could the Russian people forget their quarrels and return to the old traditional ways.[4] Still others thought of it as a temporary bridge to a monarchy, and a few envisaged a new strong church rising above the ruins of the old political system and rebuilding the House of God rather than the house of man. Only a very few of the 1905 revolutionaries were against it, and although they spoke out strongly, it made almost no impression on the Sobor[5]. The project was officially introduced on September 11, by Bishop Mitrofan of the Don but discussion was postponed until October 14.

From October 14th to October 25th, the discussion of the proposal took place. Then on October 25th, the Provisional Government was overthrown. On October 28th, when the Sobor again met, there was street fighting in Moscow. Metropolitan Tikhon celebrated a solemn prayer service Te Deum for peace, and then he suggested that, in view of the crisis, the debate be stopped and a vote taken, but still the opposition insisted on the continuation of the discussions. Speeches continued until October 30th, at which time Tikhon again suggested a vote. Fighting continued in the streets, and the very existence of the Sobor was precarious. When queried about the number in attendance, Tikhon mistakenly estimated that there was a quorum and referred to former elections of Patriarchs when as few as 220 votes had been cast. The actual proposal to elect a Patriarch was carried by 141 votes against 112, with 12 abstaining. Actually this was less than half of the original Sobor members, and therefore no quorum, and only one quarter of the members carried the responsibility of the decision. However, since there was no objection when the later voting took place, it is reasonably certain that the absent members must have been satisfied with the decision.

Along with the decision to restore the patriarchate, the respective spheres of power were worked out. On November 4th, it was ruled that the supreme authority, legislative, administrative, judicial, and supervisory, belonged to the Sobor which was to meet periodically, but the Patriarch was to head the ecclesiastical administration in the interim periods, being responsible to the Sobor when it met. The Patriarch was to be first among bishops of equal rank, but the bishops were equal to him.

During the last excited days of October, a constant bombardment was going on in the streets. The main target was the Kremlin, where a group of young cadets had entrenched themselves and were making a last-ditch stand. An appeal was made by the Sobor to the Military Revolutionary Committee to cease fighting, for great concern was felt over the holy places of the Kremlin, which in fact, suffered severely from artillery fire.[6] Tikhon, at the head of a committee from the Sobor went to the Kremlin during the actual fighting. So frightful was the carnage that all but two of the committee turned back, and the Sobor was in an uproar, fearing for the lives of the churchmen. Tikhon ascertained the damage to the Kremlin and came back to report to the Sobor. A plan was made for an enormous Krestny Hod[7] around the fighting area to stop the bloodshed, but the fighting ended almost immediately afterward, on November 4th.

On October 31st, nominations of candidates took place after the decision had been made that the election of the Patriarch was to follow the historical pattern used in the seventeenth century. On the first ballot,[8] Archbishop Antony of Kharkov received 101 votes. Archbishop Arseny of Novgorod was second with 27 votes, and Metropolitan Tikhon was third with 23 votes. On the second ballot, only the top three contenders were considered. Archbishop Antony got 159 votes, four more than needed for nomination, whereas Archbishop Arseny got 148 votes and Metropolitan Tikhon received 125 votes. On the third ballot, Arseny received enough votes for nomination and it was not until the fourth ballot that Tikhon got the necessary number to be one of the nominees[9].

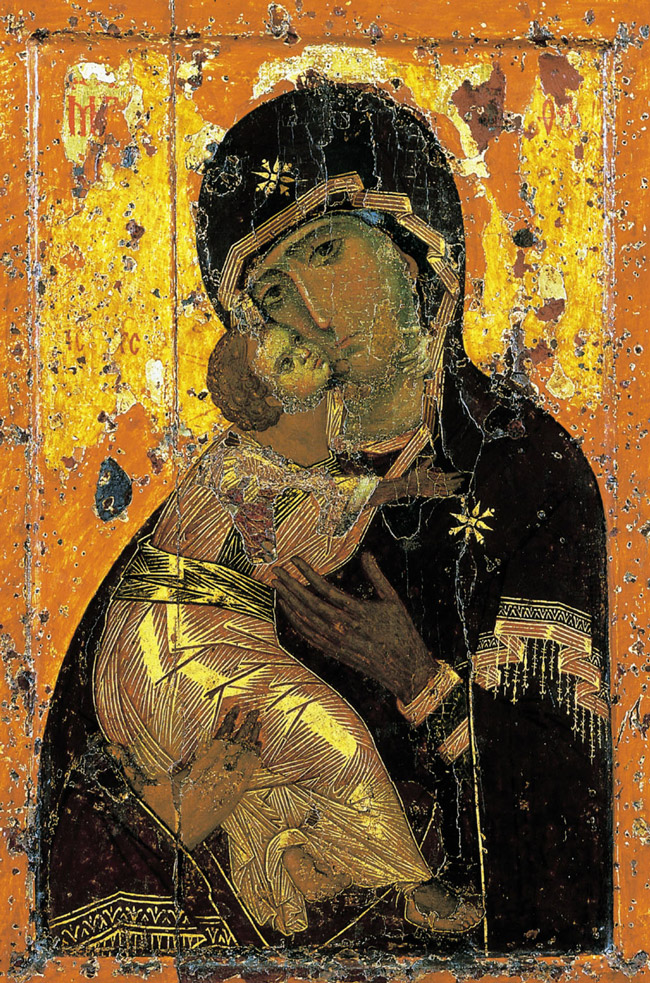

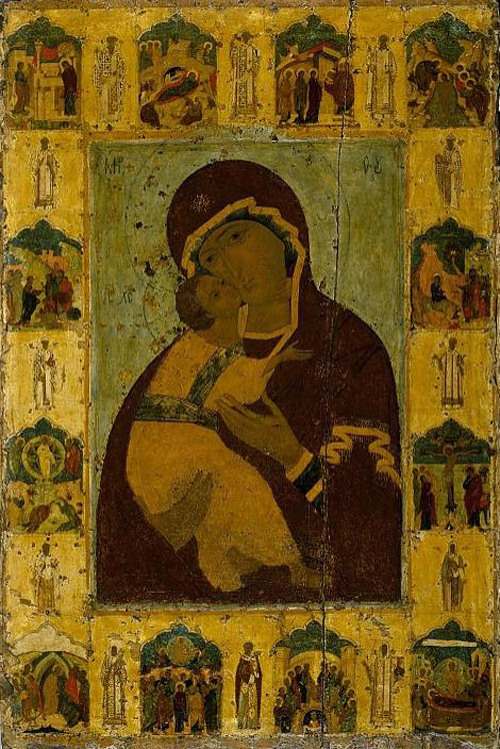

The names of the three officially nominated candidates were placed on separate slips of paper, set in a blessed urn, and put before the most famous of all Russian icons, the St. Vladimir icon of the Virgin[10]. The icon had been moved from its usual spot[11] in the Cathedral of the Assumption to the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour for this ceremony. All night, the urn remained before the icon dimly lit by flickering candles. The following morning a long and solumn liturgy was celebrated by Metropolitan Vladimir[12] before the icon and then by a prearranged choice a saintly staretz[13] Alexis of Zosimov[14] drew out one of the names. Turning to Metropolitan Vladimir, he handed him the slip, and the Metropolitan crossing himself read out, “Tikhon, Metropolitan of Moscow, Axios!” [15] Like a spark igniting dry wood, the entire church was filled with shouts of “Axios, Axios!” Above it all, the choir intoned, “We praise thee, O Lord.”

At the end of the service, amid pandemonium, the bishops filed out of the church. Suddenly, from among the milling crowds, part of which were obviously hostile to the event which had just taken place, a half-insane woman with long flowing hair rushed up to Bishop Eulogius and shouted:

“Not long, not long will you celebrate! Soon your bishop will be murdered.”[16]

During the actual drawing of the name, Tikhon had remained at the Holy Trinity Monastery hostel in Moscow and a delegation headed by Metropolitan Vladimir was sent to inform him that he had been chosen Patriarch of all Russia. On hearing the news, Tikhon at once took a binding vow to defend the Holy Orthodox Russian Church until his death. There is a very clear picture of Tikhon, the man, in his informal acceptance speech to the delegation, and fortunately, a copy of this still exists, for he seldom wrote out his speeches, preferring to speak extemporaneously, and left no dogmatic writings or papers other than a few official documents. Here it is:

Beloved in Christ, fathers and brethren; I have just uttered the prescribed words: “I thank and accept and say nothing against.” Of course, enormous is my gratitude to the Lord for the mercy bestowed on me. Great also is my gratitude to the members of the Sacred all-Russian Sobor for the high honor of my election into the members of candidates for the Patriarchate. But arguing, as a man, I could say a lot against my present election. Your news about my election for the Patriarchate is to me that scroll on which was written, “Weeping, sighing, and sorrow,” which scroll had to be eaten by the prophet Ezekiel[17]. “And he spread it before me; and it was written within and without: and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe.” Moreover he said unto me, Son of Man, eat that thou findist; eat this roll, and go speak unto the house of Israel.” How many tears will I have to swallow or how many sighs emit in my forthcoming Patriarchal office and especially in the present woeful year. Like the ancient leader of the Hebrews, Moses, I shall have to say to the Lord: “And Moses said unto the Lord, wherefore hast thou afflicted thy servant? and wherefore have I not found favour in thy sight, that thou layest the burden of all this people upon me? Have I conceived all this people? Have I begotten them, that thou shouldest say unto me, Carry them in thy bosom, as a nursing father beareth the sucking child, unyo the land which thou swarest unto their fathers? Whence should I have flesh to give unto all this people? For they weep unto me, saying, Give us flesh, that we may eat. I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me”[18]. From now on I am entrusted with the care for all the Russian churches, and what awaits me is the gradual dying for them all my days. Who is content with this even amongst those who are firmer than I? But let the will of the Lord be done, I am strengthened by the fact that I have not sought this election. It came to me without my wish, even without the wish of men, according to the lot of God. I trust that the Lord who had called me, will Himself help me by His all-powerful grace to carry the burden which is placed on me and will make it a light burden. Let it be a comfort and encouragement for me that my election occurs not without the wish of the most blessed Virgin. Twice she, by the coming of her holy icon Vladimir in the church of Christ the Saviour, is present at my election. This time the lot itself has been taken from her miracle-working icon. It is as if I were placing myself under her high protection. May she, the all powerful, stretch out to me, who is so weak, the hand of her support and may she deliver this town and the whole Russian land from all need and sorrow.[19]

Throughout his whole life, Tikhon made frequent references to his veneration for the Virgin Mary and felt that he had placed himself in her keeping. In this acceptance speech based on quotations from Ezekiel and Numbers, he sincerely mourned that he had been elected, feeling that he had not the strength to bear such a cross, but then, with a “God’s will be done,” he referred to the twofold intervention of the Virgin Mary in his life through her miraculous icon of St. Vladimir. The original elevation of Tikhon to Metropolitan of Moscow, done by the revolutionary method of election rather than by synod appointment, had been done before the Vladimir icon in the Cathedral of the Assumption. Now again, when the actual patriarchal lot had been drawn as it were from the icon itself, he was again chosen against his own personal will, so he viewed it as divine intervention and humbly bowed to the will of God.

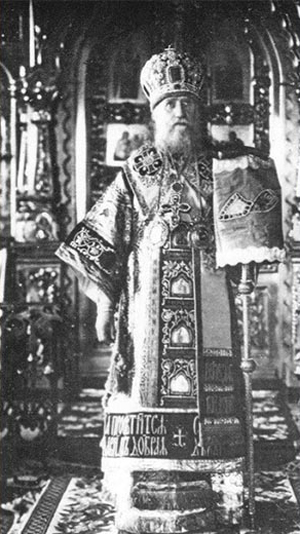

That Tikhon should take such a view of the situation is not surprising, for certainly the original voting would seem to indicate that the Sobor had desired the strength and fighting qualities of a man like Archbishop Antony or even Arseny, while Tikhon quite obviously was viewed as too mild and retiring for such a controversial position. Nevertheless, the election of Tikhon was accepted by all[20], and immediate preparations were begun for the installation ceremony. A committee was appointed by the Sobor, headed by Metropolitan Platon, who with two laymen had to seek permission from the Military Revolutionary Committee to neutralize the Kremlin and to celebrate the ceremony of installation in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. On November 8th, Metropolitan Platon reported to the Sobor that permission had been granted and that immediate research must be done to determine how the ceremony traditionally had been performed. The service of enthronement was worked out and actual implements of former enthronements were resurrected from the Kremlin. Oddly enough, the Klobuk[21] and mantle of Patriarch Nikon fitted Tikhon without alteration. The old patriarchal throne[22] of the Uspensky Cathedral was used, and the ancient staff of Metropolitan Peter of Moscow was handed to Tikhon when it was time for his sermon[23].

During this time of preparation, Metropolitan Tikhon went to the Troitsky-Sergievsky Monastery to prepare himself spiritually for the coming burdens. The Sobor continued its work, but without the new patriarch as chairman. A public funeral service was held for the killed cadets in the Kremlin and then, because of so many requests by relatives of the men who were killed on the Communist side, the Sobor also conducted a public funeral for the dead Bolsheviks. This, as the Sobor stated, was to comfort the relatives of those misguided soldiers. The new government took no part in either funeral.

On November 21, 1917, amid the ringing of the famous bells of Ivan Veliky[24], Vasily Ivanovich Bellavin was consecrated His Holiness, Tikhon, Patriarch of all Russia, in the Uspensky Cathedral. When the ceremony was completed and the liturgy performed, the first and second metropolitans conducted him to the patriarchal throne. There Metropolitan Vladimir, soon to be murdered by the Communists, presented him with the staff of Metropolitan Peter of Moscow, and the new Patriarch preached his first sermon.

It is precisely at the greatest moment in his life that Tikhon’s humble yet strong conviction of the Virgin Mary’s guidance gave him such joy. He delighted in the fact that the installation ceremony was on the anniversary of the day when the Virgin was presented in the Temple and likened the strangeness of a young girl penetrating into the Holy of Holies to the equally unbelievable restoration of the patriarchate. He saw the restoration at such a time as a sign of the Lord’s mercy to the poverty of spirit of the Russian realm and then came out with a warning to those who were unfaithful and disobedient. He lamented the destruction of holy places, the sons of Russia who had forgotten God’s commandments, and yet, heeding God’s words, said that the Church would not desert the strayed lambs but would tend them, seek them out, and return them to the ways of righteousness. Clothing his words in the special vocabulary of the church, Tikhon laid out the path he followed throughout the rest of his life both as patriarch and as a man[25].

At the end of the sermon, an enormous procession was formed of the clergy and people, and it wound its way around the Kremlin. On all sides, the people knelt to receive the Patriarchal blessing. During the entire ceremony, Bolshevik solders had been guarding the Uspensky Cathedral and attracting attention by laughing and smoking contemptuously. As the clergy came out of the church, the people surrounding them formed a barrier between the clergy and the soldiers. With the appearance of the clergy carrying icons and banners, the laughing grew more boisterous, but as the blue velvet mantle of Nikon covering the Patriarch’s shoulders appeared through the crowd, all grew silent. Suddenly one, then two, then all the soldiers broke through the protective barrier of the faithful and threw themselves at the feet of Tikhon, completely blocking his passage. Only when the Patriarch had blessed them many times would they open the way for the procession and join in the slow-moving line of people joyously following the Patriarch[26].

What was this man, Vasily Ivanovich Bellavin, like? At the early age of fifty-two, he was called on to bear the responsibilities of the only institution surviving a bloody revolution. Yet the fact of survival was still precarious, for attacks from all sides already had begun. Although his very life was in constant danger, this was probably the least of Tikhon’s worries, for on numerous occasions, he showed a complete lack of interest in his own safety. The safety and continuation of the Church to which he was wedded, however, became a burden that he never afterward forgot. That he was fully aware of this burden is shown by his acceptance speech to the delegation at the Holy Trinity Hostel in Moscow. What character traits armed him for this position of almost unbearable responsibilities?

One of the main traits that always is always mentioned in the few accounts[27] of those who knew him personally was his real humility. This has been quite obvious to the present writer who in examining the few extant writings attributable to the Patriarch, can find only one to anything personal, that is, the above mentioned remark about his old mother. It is impossible to find out the man’s likes and dislikes, friends, family, interests, or habits from anything he said or wrote. A typical incident was recorded by Metropolitan Anastassy[28], who knew Tikhon personally and worked in the Synod with him. He recalled that during the 1917 Sobor, Tikhon had as guests staying with him Agafangel[29], Arseny of Novgorod, Vladimir of Kiev and himself. Vladimir of Kiev was highest in rank and as such was first at the table and given the best room. After Tikhon became Patriarch, he insisted that Vladimir retain the same privileges and refused to outrank him in protocol[30]. If one is familiar with the ceremony of the Eastern churches, one can appreciate what a surprising attitude Tikhon here showed. The simplicity with which Tikhon lived, the lack of attendants during his travels, the difficulty he had in displaying pomp even when called on to do so, as in Poland, reveal the innate humility and disregard of self that he demonstrated throughout his entire life.

Tikhon’s very mildness and gentleness were misleading on first acquaintance, and many took it for weakness. His enemies have tried to paint him as an ornate figurehead, though their arguments do not hold up when faced with the facts. He could be extremely stubborn in both small and great things. A later description of his dealings not only with the Bolsheviks but also with the church Synod councils will fully reveal his strength of character, but the following anecdote demonstrates his strong-mindedness even in a small matter.

During his five years of rectorship at Kholm, an unpleasant situation came to a head concerning teacher’s lodgings. Originally, when the student body had numbered only seventy-five, one section of the dormitory had been turned over to the teachers as living quarters without payment of rent. The Kholm Seminary was the only seminary in Russia where such a privilege had been extended to teachers. But with the years, the student body had more than doubled, and the housing of students was woefully inadequate. Along with the increased overcrowding of students, the teachers began to turn their quarters into slums. Nursemaids, cooks, and servants, all were brought in to live in already overcrowded quarters; children had room to play only in the halls and on the stairway, and the quarrelling and noise raised a continual din in the seminary. Gently but steadily, the rector induced one wife after another to insist that her husband move into town, and by constant persuasion, the rector succeeded in clearing the entire dormitory and turning it over to the students[31].

Frequent reference has been made to Tikhon’s ever ready sense of humor even under the most trying experiences. Perhaps this was one of his most endearing qualities to those who surrounded him, for there was little to relieve the constant tension of the threats and attacks from the Bolsheviks. One of his visitors who had an audience late in 1924, soon after the Patriarch had seen his oldest and dearest friend, killed by the shot that was meant for him, said that the Patriarch still had the courage to laugh and cheer those who came to him for comfort. She spoke to him of her troubles. Her story was the same one of persecution, famine, loss of dear ones, which he must have heard hundreds of times before. He comforted her and then, as she was about to leave, she suddenly remembered she had brought a picture of him. Without thinking, she asked for his autograph and the patriarch with a quick smile said. “But I am illiterate—I cannot sign my name.” A moment later he acceded to her request, and she carried away with her not only comfort but also the memory of a short moment of fun in her dreary life[32].

Tikhon’s appearance was a very Russian one. He is described as tall and blonde[33]. His hair had a tendency to curl, and the most striking feature of his face was his deep-set, very blue eyes. His photographs, all taken after he became Patriarch, show a man with a kindly face, a large broad Slavic nose, and a shorter beard than one is accustomed to seeing on the Russian clergy. Although he died at the early age of sixty, his pictures show that he was aged far beyond his years and extremely careworn. That he suffered greatly is obvious, and in the photograph taken of him at his death, he looks like a man of ninety who died in great agony.

[1] Working from the statistics of John S. Curtiss, The Russian Church and the Soviet State (Boston, 1953); Matthew Spinka, The Church and the Russian Revolution (New York, 1927); Serge Bolshakoff, The Christian Church and the Soviet State (New York, 1942); and N. Zernov, The Russians and Their Church (New York, 1945), the following breakdown can be given. There were 564 delegates in all, including the pre-sobor council who were considered ex-officio members. There were 265 clerics and 278 laymen composed as follows: clerics: 10 metropolitans, 17 archbishops, 53 bishops, 2 protopresbyters, 15 archimandrates, 2 igumens, 3 hieromonks, 5 mitred archpriests, 67 archpriests, 55 priests, 2 protodeacons, 8 deacons, 26 psaltits; laymen: 14 active military, 20 State Duma and State Council members, 8 merchants, 33 peasants and farmers, 2 Cossacks, 12 delegates of theological academics, 13 delagates from the Academy of Science and universities, 42 governement officials and civil servants, 22 lawyers and court officials, 133 others.

[2] The complete list of Patriarchs up to 1700 is as follows: Job (1589–1607), Hermogen (1607–1612), Philaret (1619–1633), Joasaph I (1634–1640), Joseph (1642–1652), Nikon (1652–1666), Joasaph II (1666–1672), Pitirim (1672–1674), Joachim (1674–1690), Adrian (1690–1700)

[3] This was an obvious reference to St Hermogen’s heroic activities.

[4] One of the peasant representatives at the council made the following statement, “We have no longer a tsar—a father whom we could love. It is impossible to love the synod, therefore we peasants wish to have a patriarch.” Michael Polsky, Новые M ученики Россi йскiе [New Martyrs of Russia] (Jordanville, NY, 1949), 90.

[5] In fact the restoration of the patriarchate was an extremely contentious issue that was intensely debated, with the debate centering on whether the patriarchate contradicted the principle of sobornost’. The question became more urgent after the Bolshevik seizure of power. —S. M. K.

[6] Thomas Whittemore, “The Rebirth of Religion in Russia,” National Geographic 34 (1918): 378–401, published an eye-witness account of the destruction of the Kremlin by the fratricidal war between the Bolsheviks and the cadets. He visited the scene a few days after the Kremlin fell and gave a graphic description of the Austrian, German, Latvian, and Russian Bolshevik soldiers who were lounging about, writing obscene remarks on the wall, and either looting or wantonly destroying whatever struck their fancy. Enormous pools of blood were still to be traced by the stains and foot tracks through them. A shell had struck the central dome of the five domes of the Dormition Cathedral, leaving gaping holes and ruining centuries-old frescoes. All window glass was gone, and the altar and sanctuary were filled with debris of glass, bricks, and dirt. The Chudov Monastery was punctured with great shell-holes, relics were scattered, and precious icons were destroyed. The Church of St Nicholas, containing relics honored by all Christendom, was particularly defiled by filthy writings in both Russian and German, and the place where once the relics had been kept was turned into an outhouse. The porch of the Annunciation Cathedral, where Ivan IV admired the comet, was shot off. The cathedral of the Archangel Michael, the church of the Deposition of the Robe, the chapel of the icon of the Theotokos of the Caves, and the church of the Forerunner all fell beneath the cannonading. The patriarchal sacristy was turned into a rubbish heap with all the ancient treasures. A book of the Holy Gospels of 1115 was ruined; miters, crosses, vessels, and church utensils of former patriarchs were all destroyed; and ruthless looters were acting as scavengers among the ruins. Church after church was either partially or completely ruined, and the orgy of chaos was completed by the unchecked pillaging.

[7] A krestniy khod is a religious procession outside or around the church headed by clerics carrying banners and crosses, usually in honor of some religious object or event.

[8] Archbishop Antony (Khrapovitsky; 1863–1936), later metropolitan and first hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad, was one of the most brilliant and well-educated churchmen of his day.

[9] On the first round of elections, on October 30, it was Archbishop Kirill (Smirnov) of Tambov who received the second highest number of votes (27). On the following day, during the second round of voting, members were instructed to write three names on their ballots, and only the name that received an absolute majority could be considered a candidate. On the third round, members were instructed to write only two names and could not vote for Archbishop Antony, since he was already a candidate. —S. M. K.

[10] The Vladimir Icon of the Virgin was brought to Russia from Constantinople no later than the second quarter of the twelfth century. In 1155, it was removed to the Suzdal lands from Kiev and, in 1161, placed in the Dormition Cathedral in Vladimir. In 1395, it was transferred to Moscow, to the Dormition Cathedral, and taken annually in four cross-processions. During the siege of 1812, the icon was transferred to Vladimir and Murom but returned when Napoleon retreated. From the earliest times, repeated and documented miracles have been caused by the presence of the icon, until it became the most holy object of all Russia and the icon most venerated by the people.

[11] Metropolitan Evlogy, Путь моей жизни (Paris, 1947), spoke of the extreme difficulty that the churchmen had moving the icon from the Dormition Cathedral to Christ the Saviour Cathedral.

[12] Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev was chairman of the council before Tikhon was elected as president. On February 7, 1918, he was brutally abducted from the Monastery of the Caves in Kiev and murdered by a small band of assassins.

[13] Staretz is a saintly monk who has achieved such spiritual growth that he is expressly able to teach others.

[14] Alexis (Soloviev) was a monk of the Zosimov monastery, a monastery of the strictest rule whose members lived in solitude and under vows of silence. Alexis had been a member of the preconciliar committee.

[15] Axios is the Greek word meaning “he is worthy.”

[16] Related by Metropolitan Evlogy in Путь моей жизни.

[17] And he said unto me, Son of man, stand upon thy feet, and I will speak unto thee. And the spirit entered into me when he spake unto me, and set me upon my feet, that I heard him that spake unto me. And he said unto me, Son of man, I send thee to the children of Israel, to a rebellious nation that hath rebelled against me: they and their fathers have transgressed against me, even unto this very day. For they are impudent children and stiffhearted. I do send thee unto them; and thou shalt say unto them, Thus saith the Lord GOD. And they, whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear, (for they are a rebellious house,) yet shall know that there hath been a prophet among them. And thou, son of man, be not afraid of them, neither be afraid of their words, though briers and thorns be with thee, and thou dost dwell among scorpions: be not afraid of their words, nor be dismayed at their looks, though they be a rebellious house. And thou shalt speak my words unto them, whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear: for they are most rebellious. But thou, son of man, hear what I say unto thee; Be not thou rebellious like that rebellious house: open thy mouth, and eat that I give thee. And when I looked, behold, an hand was sent unto me; and, lo, a roll of a book was therein; And he spread it before me; and it was written within and without: and there was written therein lamentations, and mourning, and woe.

Moreover he said unto me, Son of man, eat that thou findest; eat this roll, and go speak unto the house of Israel. So I opened my mouth, and he caused me to eat that roll. And he said unto me, Son of man, cause thy belly to eat, and fill thy bowels with this roll that I give thee. Then did I eat it; and it was in my mouth as honey for sweetness. And he said unto me, Son of man, go, get thee unto the house of Israel, and speak with my words unto them. Ezekiel 2; 3 1–4

[18] Then Moses heard the people weep throughout their families, every man in the door of his tent: and the anger of the LORD was kindled greatly; Moses also was displeased. And Moses said unto the LORD, Wherefore hast thou afflicted thy servant? and wherefore have I not found favour in thy sight, that thou layest the burden of all this people upon me? Have I conceived all this people? have I begotten them, that thou shouldest say unto me, Carry them in thy bosom, as a nursing father beareth the sucking child, unto the land which thou swarest unto their fathers? Whence should I have flesh to give unto all this people? for they weep unto me, saying, Give us flesh, that we may eat. I am not able to bear all this people alone, because it is too heavy for me. And if thou deal thus with me, kill me, I pray thee, out of hand, if I have found favour in thy sight; and let me not see my wretchedness. And the LORD said unto Moses, Gather unto me seventy men of the elders of Israel, whom thou knowest to be the elders of the people, and officers over them; and bring them unto the tabernacle of the congregation, that they may stand there with thee. And I will come down and talk with thee there: and I will take of the spirit which is upon thee, and will put it upon them; and they shall bear the burden of the people with thee, that thou bear it not thyself alone. Numbers 11 10–17

[19] Polsky, Новые Mученики Россiйскiе [New Martyrs of Russia], 91 (translated by the writer).

[20] After the installation ceremony, telegrams poured in from across Russia, congratulating both the new patriarch and the council. Curtiss, The Russian Church and the Soviet State, 39.

[21] The klobuk is a white-rounded headdress worn by the patriarch.

[22] All during the ceremony of enthronement, the patriarchal throne was next to the empty throne of the tsar.

[23] Whenever a bishop gives a sermon, he is handed his staff, which he holds during the actual speech.

[24] Ivan the Great is the most famous bell tower in Moscow.

[25] Polsky, Новые Mученики Россiйскiе [New Martyrs of Russia], 92–93.

[26] Polsky, Ibid., 93.

[27] Evlogy, Путь моей жизни; Polsky, Новые Mученики Россiйскiе [New Martyrs of Russia]; Rozhdestvensky, His Holiness Tikhon; Metropolitan Anastassy, Памяти Святѣйшаго Патрiарха Тихона [In memory of the Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon] (Jordanville, NY, 1950).

[28] Archbishop Anastassy (Gribanovsky) of Kishinev and Khotin strongly supported the revival of the patriarchate. In 1936 he became the first hierarch of the Russian Church Abroad. ¶ Metropolitan Anastassy retired in 1964 and reposed next year. —Ed.

[29] Metropolitan Agathangel of Yaroslavl’ was one of Tikhon’s most trusted supporters and later was designated as Tikhon’s deputy in 1922.

[30] Anastassy, Памяти Святѣйшаго Патрiарха Тихона [In Memory of the Most Holy Patriarch Tikhon], 21, footnote.

[31] This story was recorded by Metropolitan Evlogy, Путь моей жизни, from actual experience, for Evlogy had been a teacher at the Kholm Seminary when Tikhon was rector.

[32] “Лѣтопись Россiи: московскiе воспоминанiя 1923–1927,” Лúтопись: органъ православной культуры 1 (1937): 64, 65.

[33] The physical description of Patriarch Tikhon was given to the present writer by Metropolitan Anastassy who knew him well.

By Jane Swan

Orthodox Life, No. 2, March-April 1964, pp. 4-15

Pas de commentaire