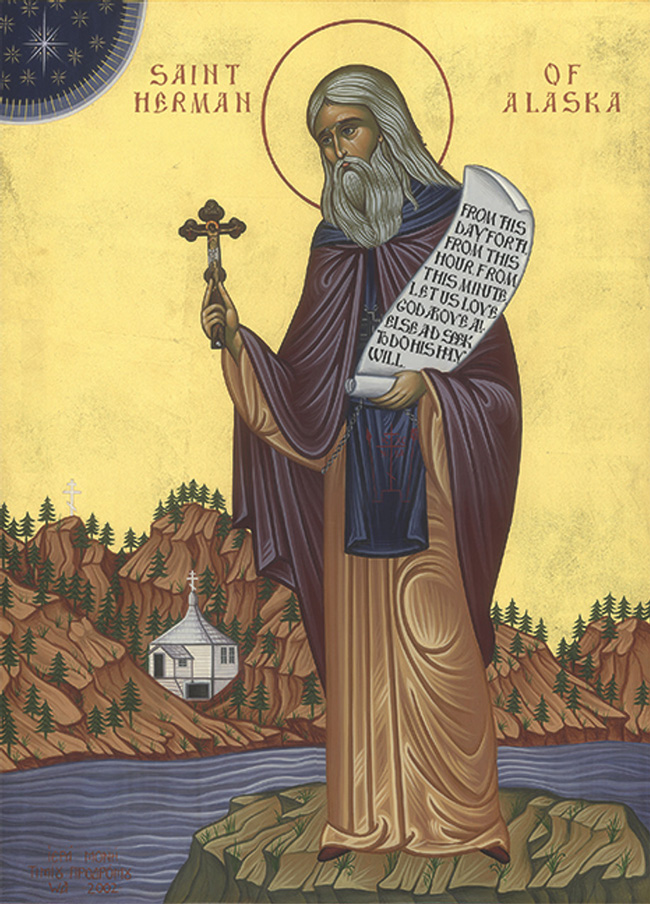

Blessed dweller of the northern wilds

and gracious intercessor for the whole worlds

teacher of the Orthodox Faith, good and most wonderful enlightener,

adornment of Alaska and joy of all America,

Holy Father Herman, pray that Christ, the King of Glory, may save our souls. [1]

Though not yet canonized, Father Herman of Alaska, as his life and miracles attest, may already he justly called America’s first Orthodox Saint. His relics are preserved today on Spruce Island. The following account of his life was the first to appear in English in America. It was written by an American expert on the North Pacific and was first printed early in this century in Pullman, Washington.

The Alaska tourist who visits Kodiak in the summer never forgets the beauty of the island, the arcadian village of St. Paul, the blue sea, the green hills, the grassy slopes, the flowery valleys, the babbling brooks, the plaintive note of the golden crowned sparrow. Kodiak is well worth remembering for other reasons: it is of historic importance, it is a sacred spot. The first Christian missionaries in the American Northwest landed on this island and the first Christian church in our North Pacific was built in this village. There is still another reason: for over forty years a man of God, Father Herman, lived and labored among the people of Kodiak and the neighboring islands. They still revere his memory, treasure his sayings, glory in his deeds, and adore him as a saint. It is the purpose of this little book to tell the story of this holy man as it is told by the natives of Kodiak and by his brother monks.

Father Herman was born not far from Moscow in the year 1756; but neither the exact place of his birth nor his name before becoming a monk is known. It would seem that his parents were of the merchant class and they gave him some educational advantages, enough to read the New Testament and the Lives of the Saints. At the age of sixteen he entered the Troitsky-Sergiev Monastery, but did not live in the monastery proper but in one of its isolated stations near the Gulf of Finland, where he was undisturbed in his devotions. While in this place he had reason to believe that the Holy Virgin had taken him under her special care. A sore broke out under his chin, causing him much suffering and slowly undermining his strength. In his sorrow he spent the whole night praying and weeping before the image of Our Lady. Towards the morning he wiped the picture with a cloth, which he then wrapped over the sore, and fell on the floor exhausted. In his sleep he saw the Virgin standing near him and felt her touching his swollen face. He woke with a start and found himself well; the sore was gone and only a slight scar was left to remind him of the miraculous cure.

In this deserted spot he lived five or six years and then entered the Valaam Monastery, situated on Valaam Island in Lake Ladoga. Father Herman was attracted by the solitude of Valaam, which during eight months of the year is ice-bound and during the other four months is reached only with difficulty. The monastery was far removed from the temptations of the world and was famed for its piety. Father Herman’s attractive personality and kindly ways soon made him a favorite with the other monks, so much so that even at this day they speak of him as the holiest man that has ever gone from them. They point to the place named after him Hermanova, where he was wont to wander off and pray for days at a time until the brothers had to go and bring him back. They tell of his religious ardor, of his gentleness, and of his sweet tenor voice, which was like that of an angel. Father Herman had the soul of a poet and there was much about the monastery and the island that appealed to his sense of beauty: the flowery fields, the shady forests, the wild birds, the snow-clad trees, the ice-covered lake, the mighty wind and raging storm. It was one of his duties to catch the fish with which to feed the hungry multitudes who came to pray. On such occasions Father Herman would pull away from shore and, after casting his nets, sit and contemplate in secret silence his beloved Valaam, its white walls and green woods, golden domes and blue sky, picturesque chapels and emerald isles, holy shrines and towering cliffs. From afar he watched the procession of the pilgrim bands with banners flying and candles glimmering and listened to the sweet music and the chiming of the bells as they came floating through the balmy air and over the silvery sea. To the fisherman Valaam was Jerusalem the Golden.

O, sweet and blessed country,

The home of God’s elect.

But more than his surroundings he loved his fellow monks, their simplicity, their humility, their guilelessness, their childlikeness. Their time was not spent in scolastic disputations and literary compositions, but in toiling in the fields and working in the shops, in feeding the hungry and praying with the dying. Years afterwards, when enduring the curses of Baranov and the sneers of his minions, Father Herman’s mind fondly turned to the days of his young manhood, to his Valaam, to his brothers. In a letter written to the abbot in 1795, he says: “The frightful places of Siberia cannot destroy, the black forests cannot hide, the mighty rivers cannot efface, the stormy ocean cannot put out the warm affection that I have for my beloved Valaam. Often I close my eyes, and see you across the waters.”

When in 1793 the Holy Synod decided to organize a Kodiak Mission and called for volunteers to go to America to preach the Gospel to the Aleuts, Father Herman was one of the first to offer himself and one of the first to be accepted. This was no ordinary undertaking, it was the first mission ever sent out by Russia across the sea. The men selected were the best the monastery had to offer, they were full of the spirit of the Apostles, and they were eager to give their lives to advance the Kingdom of God. They were eight in number: Archimandrite Joasaph the leader, monks Juvenaly, Macary, Afanasy, Joasaph, Herman, deacons Stephen and Nectary. These men were plain peasant and fisher folk of limited education and restricted outlook, but zealous in the faith and ardent in their devotions?[2] They had never been far from their village homes and out-of-the-way monasteries, and the journey to the new field of labor was an important event in their lives. They set out from Moscow on January 22, 1794, and moved gradually across Siberia to Okhotsk where they took ship for Kodiak, reaching their destination on September 24 of that same year.

As soon as they walked ashore the leader called his followers together on a knoll to discuss plans for the work. It is inspiring to read the account of this first religious conference in the Northwest and to note with what eagerness the brothers contended among themselves for the most difficult and dangerous task. It is said that one of the monks, while walking along the beach saw an empty skiff into which he stepped and, lifting his hands to heaven, prayed that he might be guided to a place where he could be of most service. A wind came up and blew the skiff on Nuchek and there the monk preached salvation to the heathen.

The winter that followed their arrival was a busy one for Father Herman and the other missionaries, who went from village to village telling the people of the Saviour. On May 19, 1795 the Archimandrite wrote: The Lord be praised! We have baptized more than seven thousand Americans and have performed more than two thousand marriage ceremonies… We love them and they love us; they are good but poor. They are so willing to be baptized that they have destroyed and burned their idolatrous things. We were afraid that they were naked, but God be thanked they are not altogether without modesty. their bird-skin shirts come down sufficiently far in front. During the year 1795 Hieromonk Juvenaly baptized seven hundred natives on Nuchek and all the inhabitants of Cook Inlet. In the following summer he crossed over to the mainland and exhorted the people living along the shores of Iliamna Lake to give up their polygamous and heathenish practices and lead Christian lives. Many heeded his words and were baptized; but others, led by their shamans, sought to destroy him. When he had gone from their village they waylaid him and killed him. But as the murderers started back for their home Hieromonk Juvenaly rose from the dead and followed them. Once more they discharged their arrows into his bleeding body and once more he pursued them. This happened several times. In their desperation they hacked his body into small pieces and ran away, but as they glanced back they observed a column of smoke ascending heavenward from the mutilated body.

The work so auspiciously begun aroused much interest in Russia. The Holy Synod decided to enlarge the field of labor and to increase the force of workers. It called Archimandrite loasaph to Irkutsk to be consecrated bishop so that on his return he would train and ordain native priests who should go over the length and breadth of the Northwest to carry light to those who lived in darkness. This grand conception, promising so much for the glory of God, was never realized. The ship Phoenix the first boat built in Alaska, on which the bishop with his assistants, including Fathers Makary, Stephen, and others, was returning from Okhotsk to Kodiak in 1799, foundered at sea with all on board. From this sad loss the mission never fully recovered.[3]

There were still four missionaries in America and under the guidance of Father Herman, they could have continued the work had they not been so bitterly opposed by the officers of the Russian American Company. It was the old fight between the missionary and the trader. The priests reproached Baranov and his associates for their licentious lives and for their brutal treatment of the islanders, and later brought the matter before the Holy Synod. Baranov neither forgot nor forgave this injury and he swore that he would be avenged on the informers. As soon as it became known that the bishop was lost, Baranov set about venting his wrath on Father Herman and his fellow workers. He was all-powerful, he was coarse, he was cruel. It used to be a common saying among the hunters of his day, that, “God is in Heaven, the Tsar is in Russia, Baranov is in America; let us, therefore, bow before Baranov.” He drove the monks from the natives and unmercifully abused the natives if they went near the monks. By dragging one of their number to the church and threatening to hang him from the steeple, Baranov secured the keys to the building and kept it locked after that. He was determined to hound the missionaries from the island and out of his sight; and at the same time his friends in the capital were powerful enough to oppose the petitions of the poor men to be allowed to return to Russia. They were caught between the devil Baranov and the deep Pacific Ocean. These adversities and discouragements crushed the independent spirit of Father Herman’s associates; they lost confidence in themselves and the respect of the people. After much pleading Father Nectary was allowed, in 1806, to go to Siberia; Father Afanasy, weak in body and spirit, retired to Afognak; Brother Joseph became demoralized and dragged out a pitiful existence in the village of St. Paul. Father Herman remained steadfast in the faith. Trials and tribulations made him only stronger and he would under no circumstances desert his people and let them slip back into the power of the devil. Realizing, however, that the cause of God could be advanced more quickly away from Baranov and his Satanic crew, Father Herman withdrew from their presence and opened a mission on the uninhabited island of Elovoi (Spruce), which he named New Valaam in memory of the Holy Island in Lake Ladoga.

New Valaam is a small island not many miles from Kodiak. Here the father built himself a cell, a chapel, and a house to accomodate the native orphan children. After a time a number of Aleut families settled on the island, but they lived some distance from the father, who sought a life of solitude. A man asked him once: “Father Herman, do you live alone in the forest? Do you never become lonely?” “No, I am not alone,” he said, “God is there as He is everywhere. His angels are there. Is it possible to be lonely in their society? Is it not better to be in their company than in that of people?”

A traveller who saw Father Herman in 1819 described him as of medium height and delicate constitution. His face was pale and kindly and his soft blue eyes invited confidence and bespoke sympathy. His gentle and friendly voice drew people to him, especially the children. His body was girded with a fifteen-pound chain, his shirt was a deer hide, his sandals a piece of rough leather, though at times he went barefoot, and over all he wore a patched monastic cloak. Thus scantily clad he walked over hill and dale, through snow and rain, in heat and in cold, wherever duty called him. A bench covered with a seal skin served for a bed, two bricks for a pillow, and a board for a blanket. His personal habits were simple: he ate sparingly, slept little, prayed long and worked hard. He was tolerant of the weaknesses of others and did not urge them to lead the same ascetic life he did. He was kind to wild animals, the birds and the squirrels were his companions, and the savage bear fed out of his hand.

If he led a secluded life it was not in order to escape the cares of the world, for whenever his presence could serve some useful purpose he came forth. His great object in life was to help and uplift the Aleuts, whom he regarded as mere children in need of protection and guidance. He was ever pleading for them with the officers of the company. “I, the lowest servant of these poor people,” he wrote to lanovsky, “with tears in my eyes ask this favor: be our father and protector. I have no fine speeches to make, but from the bottom of my heart I pray you to wipe the tears from the eyes of the defenseless orphans, relieve the suffering of the oppressed people and show them what it means to be merciful.”

Father Herman was a nurse of the natives in a literal as well as a figurative sense. When an epidemic broke out in Kodiak and carried off scores of people, he never left the village, but went from house to house, nursing the sick, comforting the afflicted and praying with the dying. It is no wonder that the natives loved him and came from afar to hear him tell the story of Christ and His love for them. Father Herman fed the hungry, cheered the troubled, turned strife into concord, and all who came to him discouraged he sent away with God’s peace in their hearts. He gave to the orphan children a home, he taught them to read and write, and trained them to do useful and honest work. His daily food he secured through his own efforts and with the help of his pupils. They planted gardens, caught fish, picked wild berries, and dried mushrooms. His influence over the people was remarkable. One Sunday morning he told the natives that Jesus gave His life to save humanity and that it was the duty of every person to help mankind.

When he had concluded, a young woman, Sophia Vlasova, stepped up and offered herself for God’s service. The good father saw the hand of God in this sacrifice, for at the time he was in need of a woman to look after his little children, and made Sophia the matron of the orphanage.

The Aleuts were not the only people for whom he labored. Father Herman worked with equal zeal in behalf of the white men and through his efforts many were led to give up their lives of sin and follow the teachings of the Saviour. One of his converts was Baranov’s successor, Lanovsky, who when he reached Kodiak boasted of his infidelity and spoke contemptuously of Christianity. He heard of the pious monk and invited him over to Kodiak where night after night the two men discussed questions of faith, immortality, and salvation. The simple words and strong faith of the monk sank deeply into the heart of the naval officer, and years later he and his son and daughters gave up all that they possessed and entered cloisters. Another of his converts was an educated German sea-captain in the employ of the company. He engaged the father in a religious argument and before it ended the captain acknowledged his errors, renounced the heretical doctrines of Luther, and asked to be received into the Orthodox Church.

One day the captain and officers of a Russian man-of-war invited Father Herman on board to dine with them. In the course of the conversation he put this question to them. “What do you, gentlemen, regard as most worthy of love and what do you most wish for your happiness?” One man said he desired riches, a second glory, a third a beautiful wife, a fourth the command of a fine ship. The others present expressed themselves in some similar manner. Is it not true,“ said Father Herman, “that all your wishes can be summarized in this short sentence: each of you desires that which he thinks is most worthy of love?” To this statement they all agreed. “If this is true,” he continued, “what can there be better, higher, nobler, and more worthy of love than the Lord Jesus Christ, the Creator of heaven and earth, the Author of all living beings. Who provides for all, Who loves all, and Who is the incarnation of love? Should we not above all love God, seek Him and desire Him?’ The officers were quite confused and replied that what he said was true, was self-evident. He then asked them if they loved God. ‘To be sure,” said they, ”we love God. How could anyone not love Him?” Hearing these words the old man bowed his head and said: ’I, a poor sinner, for forty years have tried to love God and I cannot say that I love Him as I should. To love God is to think of Him always, to serve Him day and night, and to do His will. Do you, gentlemen, love God in this manner, do you often pray to Him, do you always do his will?” With shame they acknowledged their short-comings. “Then let me beseech you, my friends, that from this day forth, from this hour, from this minute, you will love God above all.” The officers marveled at his words and long remembered them.

Whenever the workmen of the company got into difficulty with their officers they besought Father Herman to intercede for them. Though old, feeble, and blind, he was always ready to undertake these offices of mercy. One day he pleaded hard with the agent in Kodiak in behalf of a hunter, trying to point out to the officer the Christian duty of forgiveness and the need of charity; but it was to no purpose. The hard-heartedness of the man moved the old father to tears and he exclaimed: “Woe unto him who is not merciful, for no mercy shall be shown to him!” The wife of the agent, who was standing by, retorted by saying: “Father Herman, we are merciful and we give charity four times a year.”

What you give to the poor belongs to God and not to you. There will come a time when you, too, will be in trouble and in want and then you will know what mercy means.” Turning to the agent he added, “In two years from now you will be transferred to a less desirable place and you will then think of my words.” As he said so it came to pass: two years later the agent was carried in chains to Sitka.

Because he was so outspoken in his condemnation of all that was coarse and wicked there were some who hated him and sought to do him harm. One night a party of the company’s men invaded his cell in search of furs and money which, they claimed, he had taken from the Aleuts. They ransacked his hut from top to bottom without finding anything of value. This angered them and one of the men took up an axe and commenced tearing up the floor in the hopes of discovering something incriminating. Father Herman watched them sorrowfully and said: “My friend, you have lifted up the axe to no good purpose, for by it you shall die.” Not many months afterwards this man with others was sent to Cook Inlet to put down a native uprising and one night a hostile native stole into the camp, picked up the axe and slew him with it.

In 1834 Baron Ferdinand Wrangell, at the time a captain in the Imperial Navy, arrived in Kodiak and went unannounced to make a call on the old father, who was then seventy-eight years of age and blind. Notwithstanding that, he knew who his visitor was and greeted him with the title of “Admiral.” Captain Wrangell tried to set him right but the old man told him that on such and such a day he had been named “Admiral,” which, as it later proved, was really true.

When Father Herman first came to New Valaam, the devil and his agents tried to get him into their power. They presented themselves to him in the form of human beings to tempt him and in the shape of wild beasts to frighten him; but they wrought no evil in him for by calling on the Saints he drove them off. He was ever on guard against their machinations, and he permitted no one to engage him in conversation or to enter his cell without first making the Sign of the Cross.

As he grew older and holier the good father was allowed to see angels, he was given control over the elements, and was granted the gift of prophecy. On certain holy nights[4] he watched by the seaside for the angels to appear and dip the cross in the water, and this holy water he gave to the sick and cripples and they became whole. When an inundation threatened to submerge New Valaam Father Herman checked its force by placing the icon of the Holy Virgin on the beach and ordering the waves not to advance beyond it. Another time he saved his people from a forest fire by marking the limits beyond which the flames were not to spread. A year before it was generally known in Kodiak he told the Aleuts that the Metropolitan of Moscow had passed away. He foretold that an epidemic was coming which would kill off a large part of the native population and that those who were left living would be gathered into fewer villages. Two or three years before his death he told an agent of the company that the rime was not far off when a bishop would be appointed for Alaska. The prophecies just mentioned have already come to pass, and other prophecies made by him will come true in God’s good time.

When Father Herman realized that his days on earth were numbered and that it was time to join the saints, he called to him Sophia Vlasov with the girls and Gerasim, his helper. He asked that Sophia spend the remainder of her years on the island and that when she died she be buried at his feet. He advised the girls to marry and the same advice he gave to Gerasim, whom he asked to make his home on New Valaam. Continuing he said: “When I die, don’t send for a priest; he will never come! Do not wash my body. Put it on a board, fold my hands on my chest, place me in my monk’s mantle; with its lappets cover my face, and with the klobuk my head. If anyone wishes to bid farewell to me, let him kiss my cross. Do not show my face to anybody.”[5] Several days after the above conversation he called for Gerasim to light the candles and read from the Acts of the Apostles. While Gerasim was reading the countenance of the old father was lighted up with a heavenly light and he was heard to say, “Glory to Thee, O Lord.” He then told Gerasim to put aside the holy book, for God had granted him another week of life. At the end of that time he again summoned Gerasim and requested him to light the candles and to read from the Acts of the Apostles. In the midst of the reading Gerasim became aware that the cell was filled with light and that a halo played around the holy father’s head. Gerasim then knew that Father Herman was a saint and that he had gone to join the heavenly choir.

On the night that Father Herman died the people of Afognak Island saw hovering over New Valaam a column of light. At this wonderful sight they fell on their knees exclaiming, “Our holy man has gone from us.” In another village the people observed that same night an object like a human being borne aloft from New Valaam towards Heaven.

Gerasim and the girls became frightened at what they had witnessed and immediately dispatched a messenger to Kodiak to tell what had happened. The officer of the company sent back word not to inter the body until he came over with a priest and a casket. But before he could start, there blew up such a storm as had never been seen, and no one dared to venture out to sea for a whole month. During that whole time the body of the saint lay in his cell without any decomposition setting in. Seeing the hand of God in the storm and recalling Father Herman’s last words, Gerasim and the girls buried the father according to his wishes. Immediately the wind died down, the sea became calm, and the sun came out.

In 1842 the ship on which Bishop Innokenty was sailing from Kamachatka to Alaska ran into a severe storm which threatened to wreck it. The good bishop prayed for help to the saints, and remembering the pious Father Herman he said to himself, ‘If you have pleased God, Father Herman, make the wind change.’ Immediately a fair wind sprung up and in good time the boat was safe in the harbor of St. Paul. In gratitude for the deliverance, the bishop held a service over the grave of Father Herman.

Thirty years after the death of the saint the priest of Kodiak visited his resting place and found that the grass on the grave is ever green, summer and winter, and that the cross is as new and as sound as the day it went up.

The natives of Kodiak love to tell the story of Father Herman, Alaska’s Saint, who is so near and dear to them. He left no picturesque missions or learned colleges to speak of his achievements, but he planted Christianity in the hearts of the Aleuts and that shall endure as long as the Aleuts live. On the walls of Valaam Monastery may be seen hanging a picture of New Valaam and a likeness of Father Herman and as the monks pass by they cross themselves and pray that the time may soon come when his bones shall rest in the sacred ground of the monastery and when the Church shall officially recognize him as a saint.

[1] Troparion, Tone 4

[2] The information here is not quite correct. Rev. Hierodeacon Stephen, former officer, and Rev. Hieromonk Juvenaly, at one time a mining engineer, were not of such simple background as the author states. As for the Archimandrite loasaph (before monasticism Ivan Ilyich Bolotoff), he was the son of a priest from the Kashensky region and was educated in Tver and Jaroslavl Seminaries. After completing his studies he taught for four years in the Uglitzky Theological School and in 1784 entered the monastic life. In 1793 he was appointed head of the Ko li ik Mission as recommended by the Abbot of Valaam Monastery, Nazary, advisor to the first publication of the Philokalia in Russia. On April 10.1805 loasaph was consecrated bishop. He was the author of an extensive and systematic work published in 1805, describing life on Kodiak Island.

[3] Outline of the History of the American Orthodox Mission (in Russian), Valaam Monastery, St. Petersburg, 1894.

[4] On the feast of the Baptism of our Lord the Holy Church blesses water to be used by the faithful throughout the whole year. After 1825 there was no priest in Alaska to perform this blessing. Gerasim reported having seen an angel bless the waters of the bay for Father Herman.

[5] The face must be covered according to the monastic rules.

The Orthodox Word, 1965, Vol. 1, No. 1, January-February, pp. 3-16

Pas de commentaire