By E. Sumarokov [1]

An introduction to one of the most important Orthodox literary figures of the 19th century: translator of the Philokalia, and author of valuable works of spiritual guidance based on the Holy Fathers and his own profound spiritual experience.

I

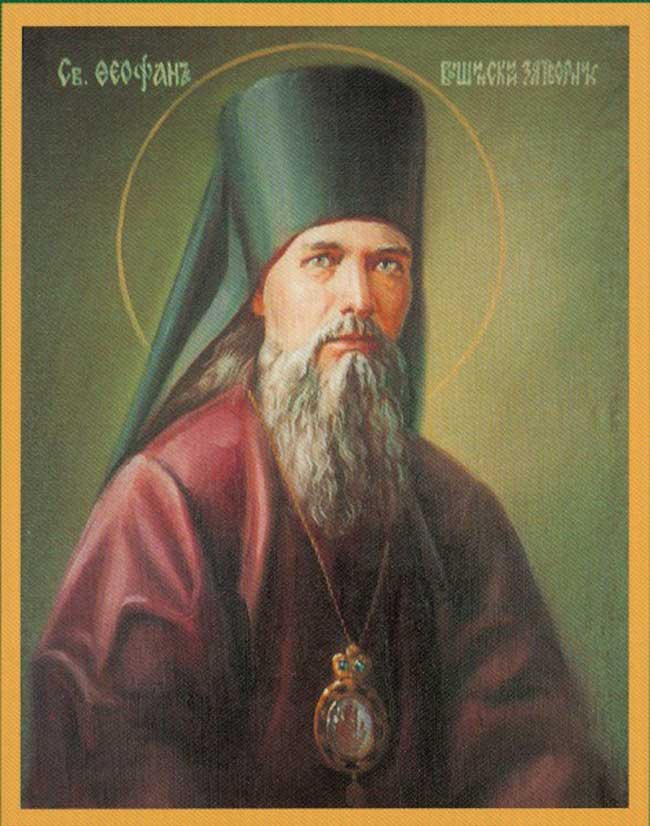

To bishop Theophan belongs an immense significance in the history of the moral development of Russian society. That thirst for complete union with God which led him into reclusion did not deprive the world and his own people of his help. Even from his remote reclusion he was a great public figure, supporting and directing thousands of people and their spiritual life.

Acquiring great spiritual experience by means of complete self-renunciation and strict daily asceticism, Bp. Theophan generously shared with all who had need of it the treasures of his spiritual experience. No one who appealed to him in writing was denied advice. But he exerted a much wider influence by means of his books. How to live a Christian life; how, amidst the slough of temptations, misfortunes, weaknesses, the weight of our sinful habits, not to fall into despair; how to desire salvation for oneself and begin the work of moral perfection; how to do battle on this path step by step, and to enter ever more deeply into the saving enclosure of the Church: it is of this that the books of Bp. Theophan speak.

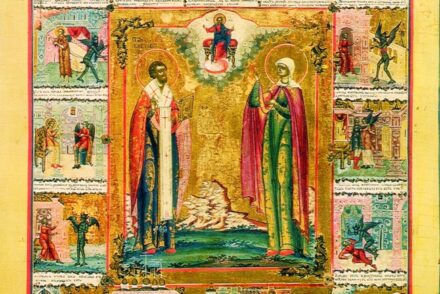

In this connection he resembles the great laborer on the field of the spiritual rebirth of the Russian people, St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, who wrote so much, so well, and so penetratingly on the salvation of the human soul amid the dangers of this sinful world.

Behind all the spiritual wisdom that is expressed in his books stands the pure image of a great ascetic. Every word of Bp. Theophan produces all the stronger an impression for having been imprinted by his life. When he repeats: “Do not gravitate to the earth. All is corruptible; only the happiness beyond the grave is eternal, unchanging, true, and this happiness depends upon how we spend this life of ours!”—then as a living example of this correct view of the world and the destiny of the soul stand his own self- denial, his reclusion, his desire to take nothing from life but a striving toward God.

II

Bp. Theophan was called in the world George Vasilyevich Govorov and he was born on Jan. 10, 1815, in a village near Orel, where his father was a priest. Thus from the first impressions of his youth he lived with the Church. He studied first in the theological preparatory school in the city of Liven, then in the Orel Seminary. However difficult the severe, sometimes cruel conditions of the theological school were at that time, it gave its sons a strong mental temper.

From 1837 to 1841 he continued his education in the Kiev Theological Academy. One may confidently say that the young student often went to the caves of the Kievo-Pechersk Lavra, and amid these recollections there could have been formed in him the resolution to leave the world. Even before finishing the course he was tonsured a monk.

After his tonsure Theophan, together with other newly-tonsured monks, went off to the Lavra, to the well-known Father Partheny. The Starets told them: “You, learned monks who have taken various rules upon yourselves, remember that one thing is most necessary of all: to pray and to pray unceasingly in your mind and heart to God.”

Having finished the course with a master’s degree, Hieromonk Theophan was assigned as temporary rector of the Kiev-Sofia Theological School; later he was rector of the Novgorod Seminary and a professor and aid to the supervisor in the Petersburg Theological Academy.

This purely scholarly work did not satisfy him, and he petitioned to be discharged from academic service. He was assigned as a member of the Russian Mission in Jerusalem; then, raised to the rank of archimandrite, he was assigned as rector of the Olonetsky Seminary. He was soon transferred to Constantinople as chief priest of the embassy church, then called to Petersburg to be rector of the Theological Academy and supervisor of religious instruction in the secular schools of the capital.

On May 9, 1859, he was consecrated bishop for Tambov. Here he established a diocesan school for girls. During his stay in the Tambov See, Bp. Theophan came to love the isolated Vysha Hermitage. In the summer of 1863 he was transferred to Vladimir, where he served for three years. Here too he opened a diocesan school for girls He served in church often, travelled much throughout the diocese, preached constantly, restored churches, and wholeheartedly lived with his flock, sharing with them both joy and sorrow.

III

In 1861 Bp. Theophan was present at the opening of the relics of St. Tikhon Zadonsky. This event must have produced a very strong impression on him, since he had so much in common with St. Tikhon. He had so loved St. Tikhon from his very childhood, had always thought of him with such enthusiasm, that when the time came for the canonization of this great teacher and protector of the people, Bp. Theophan’s joy was inexpressible.

In 1866 Bp. Theophan petitioned to be relieved as Bishop of Vladimir and was appointed head of the Vysha Hermitage, and soon, at a new petition of his, he was freed even of this duty.

What reasons induced Bp. Theophan, full of strength, to leave his diocese and retire into solitude? Various are the characters and gifts of men. It was difficult for him in the midst of the world and those demands to which one must yield as a consequence of human corruption. His unlimited goodness of heart, a meekness like that of a dove, his trust of people and indulgence of them—all this indicated that it was not for him to live amidst the irreconcilable quarrels of vain worldly life. It was very difficult for him to be a leader, especially in such an important position as that of bishop. His trust could be abused; he could never give necessary reprimands. Besides this, he felt the call to devote all his energies to spiritual writing. As for himself personally, he wished to give up all his thoughts to God alone, Whom he loved so absolutely. He desired that nothing might disturb the complete communion with God that was so dear to him. And he left the world to be alone with God.

There was an example that Bp. Theophan kept constantly before his eyes: St. Tikhon, to whom he had been so drawn from his youth, and who also, leaving one diocese, became a spiritual benefactor of the whole Russian people.

To be sure, in retiring from his diocese Bp. Theophan more than anything else thought about the salvation of his own soul by means of complete dedication of every thought and breath to God. But the word of Christ was realized in him. In reclusion, invisible to people, he became a public figure of enormous magnitude. He sought only the Kingdom of God, and his great significance for the world was added to him.

On Sunday, July 2, 1866, the Bishop bade farewell to his flock. After serving the Liturgy, the Bishop gave his last sermon amidst a death-like silence, in which could be heard only an occasional quiet weeping. And there began 28 years of a solitary, full life of uninterrupted labors.

IV

The first six years the Bishop went to all services and to the early Liturgy. In church he stood without moving, without leaning, with eyes closed so as not to be distracted. On feast days he usually officiated.

Beginning in 1872, however, he discontinued all intercourse with people except for the chief priest and his confessor. He went no longer to the monastery church, but built with his own hands in his chambers a small church dedicated to the Baptism of the Lord. For the first ten years he served the Liturgy in this church every Sunday and feast day, and for the next eleven years every day. He served completely alone, sometimes in silence, but sometimes singing.

He seemed to be no longer a man, but an angel with a childlike meekness and gentleness. When people came to him on business, he said what was necessary and plunged back into prayer. He ate only enough so as not to ruin his health. Everything that he received he sent by mail to the poor, leaving himself only enough to buy necessary books. From his publications, which were quickly distributed, he received nothing, hoping only that they might be sold as cheaply as possible. In the rare moments when he was free from prayer, reading, or writing, he occupied himself with manual labor. He painted excellent icons and was skilled in woodcarving and the locksmith’s trade.

Every day Bp. Theophan received from twenty to forty letters, and he answered them all. With extraordinary sensitivity he penetrated to the spiritual situation of the writer and warmly, clearly, and in detail replied to this confession of a distressed soul.

His letters, which appeared in print after his death, strike one by their freshness, sensitivity, depth and boldness of feeling, simplicity, warm concern, cordiality.

And thus he lived, directing from his reclusion believers who came to him from afar thirsting for salvation.

A few words should be said on the books of Bp. Theophan. On everything he spoke from experience and systematically, as a man who had himself passed through the stages of spiritual development on which he wanted to lead others. His works include:

On moral theology: Letters on the Spiritual Life; Letters on the Christian Life; Miscellaneous Letters on Faith and Life; What the Spiritual Life Is and How to Dispose Oneself for it; The Path to Salvation; On Repentance, Communion, and Amendment of Life; On Prayer and Sobriety.

Commentaries on Holy Scripture: Commentaries on the Epistles of St. Paul (all, with the exception of Hebrews); Commentaries on Psalms 33, 118.

Translations: The Philokalia, in five volumes; The Ancient Monastic Statutes; Unseen Warfare; The Sermons of St. Simeon the New Theologian.

V

The life of Bp. Theophan passed unseen by the world, and death too came to him in solitude. In his last years his vision began to fail, but he did not abandon his constant work, continuing to portion his time in the same strict fashion as always. Evenings his cell attendant prepared everything for the celebration of the Liturgy. After the Liturgy the Bishop asked for tea by a knock on the wall. At one o’clock he ate—on non-fast days an egg and a glass of milk. At four o’clock he had tea, and after that no more food for the day.

Beginning January 1, 1891, there were several irregularities in his schedule. On January 6, at 4:30 in the afternoon, his cell-attendant, noting the Bishop’s weakness during these days (although he nonetheless continued to write after noon), looked into his room. The Bishop lay on the bed lifeless. His left arm rested on his breast and his right arm was folded as if for a bishop’s blessing.

For three days the body remained in the small church in his cell and for three days it was in the cathedral—and there was no corruption. When he was vested in his bishop’s vestments, the face of the dead man was brightened by a joyful smile. Bp. Theophan died at the age of 79. He was buried in the unheated Kazan Cathedral.

In Bp. Theophan’s cell everything was extremely simple, even meager. The walls were bare, the furniture old: a cupboard worth a ruble, a two-ruble chest, an old table, an old reading stand, an iron folding bed, sofas of birch wood with hard seats. There was a trunk with instruments for lathe-work, carpentry, book-binding; photographic equipment, a bench for sawing, a joiner’s bench. There was a gray cotton undercassock, a wooden panagia, a wooden pectoral cross, a telescope, a microscope, an anatomical and a geographical atlas.

And then the books—books without number, without end, in Russian, Slavonic, Greek, French, German, and English. Among them were: a complete collection of the Holy Fathers; a theological encyclopedia in French in 150 volumes; Soloviev’s History of Russia; Schlosser’s Universal History; the works of the philosophers Hegel, Fichte, Jacobi, and others; works on natural history by Humboldt, Darwin, Fichte, and others. One calls to mind his words: “It is good to understand the structure of plants, of animals, especially of man, and the laws of life; in them is revealed the wisdom of God, which is great in everything.”

In addition there were an immense number of icons, a picture of St. Seraphim of Sarov[2], and many icons painted by the Bishop himself.

The great hierarch is hidden from us in body, but his spirit lives in the divinely wise printed works which he left. In the person of Bp. Theophan, as Archbp. Nikander of Vilna has said, we have a universal Christian teacher, even though he did not speak; a public figure, though in reclusion; a preacher of the Church who was heard everywhere, even though in his last years he appeared in no Church see; a missionary-convictor of sectarian errors, even though he did not step out onto the field that was open to missionary activity; a bright lamp of Christ’s teaching for Orthodox people, even though he concealed himself from the people’s gaze; possessing scarcely a sufficiency of earthly goods, yet enriching all with the spiritual wealth of his teaching; seeking no temporal, earthly glory, yet glorified now both by people and by theological science, as well as by various institutions.

[1] From Lectures on the History of the Russian Church, Harbin, 1945, vol. 2

[2] Before his canonization, which occurred in 1903 (trans. note).

The Orthodox Word, 1966, Vol. 2, No. 3 (9), pp. 90–96

Pas de commentaire